THE ART OF FALSE POSITVES

EDU DDA DEC. 11, 2023

Summary: With curves hugely inverted, it’s quite natural to ask, what are the chances they are sending a false positive? The answer to that question depends on what you mean. Here we’ll take the first of several deeper dives into the recent history of curve/financial indications to evaluate them for their usefulness and performance. In doing so, we’ll uncover what they’re really telling us. It isn’t about another Lehman.

How accurate are these esoteric market indications we spend so much of your time on here reviewing at Eurodollar University? It’s a great question, one that needs to be asked repeatedly. You’re only as useful as your last curve shape.

Now, there are lots of these things and several different types. Over the weeks ahead I plan on occasionally highlighting one type at a time here in the DDA. Today we’ll start with my absolute favorite, though I’m still not just metaphorically upset it doesn’t exist any longer.

While eurodollar futures aren’t the namesake of this site and its operation, along with Eurodollar University they absolutely do share the same genesis. These contracts were unwisely replaced by forward rate contracts linked to term SOFR (a separate discussion for another day).

For the longest time LIBOR was the key offshore unsecured US$ benchmark. Therefore, it absolutely made sense to hedge using instruments which sought to price what that benchmark might be at various points in the future. Since the eurodollar system is unfathomably huge, those utilizing the derivatives weren’t just hedging immense portfolios, in doing so they gave us an incredibly powerful window inside the eurodollar blackhole.

Judging the effectiveness of that insight only requires reasonable standards. Sadly, few are willing to give it that much.

To start with, never, ever take these curves literally. A eurodollar futures contract was never a straight bet on where 3-month LIBOR was going to be at contract maturity. Same goes for the SOFR-based replacement, EurIBOR futures or any other forward rates. These are all about probabilities not crystal balls.

In fact, one of the key mistakes policymakers have made in the post-crisis era is the upward slope of eurodollar futures curves (they’ve continuously made the same argument against forward-OIS, too). Year after year when ST rates were pinned at zero, eurodollar futures curves were at times significantly upward sloping which officials immediately pointed out to discredit them.

Again, eurodollar futures weren’t betting that interest rates would go up at those specific times, rather the probability that ST money rates could if everything went the way it was being perceived at those various dates in time. From the zero lower bound, money/forward rate curves are going to be some degree of upward sloping even when the marketplace is incredibly pessimistic and doesn’t expect much chance of higher rates.

You’re never going to have a perfectly flat forward curve right around zero – but that’s how the FOMC and even the ECB officials used to talk about them. To be honest, they’ve used every excuse not to consider the information contained in the marketplace because so often the marketplace was betting against the genius plans of these institutions. Especially the multitudes of QEs.

From that overview, we start with one of my favorite all-time charts; it is practically artwork, especially when you let Microsoft Excel fill in some of the colors. What truly gives it that unique beauty is how clear the eurodollar cycles are throughout:

From its most basic terms, you can literally see the hedging which has the effect of flattening the curve and often dramatically. When feces and fans are getting closer and closer together, buy fecal-flinging protection like EDs (I’m going to upload this video again; it’s from the EDU membership series called The Basics which in this episode it describes how forward rate curves work and what they really mean).

To begin assessing the accuracy, we’re really more interested in the post-2008 world. We know how eurodollar futures performed in the leading period before the crisis. Though, you could actually argue the market wasn’t nearly pessimistic enough. While the information was better than you could get from stocks or from other corners of finance, reality turned out far worse than even the originally inverted curves.

Unlike most, especially central bankers, the markets learned from that lesson. Deep pessimism wouldn’t be so reluctantly priced moving forward in time.

This, however, sets up another false expectation, of sorts. When curves were heavily bid and collapsing in future episodes, did those mean to suggest a rerun of 2008? If that is how you interpreted them, then curves got the next several cycles wrong because, obviously, there was no repeat.

However, that was never really the standard nor the expectation. Not all pessimism or even really bad scenarios have to be the worst thing since the Great Depression. We have to understand what’s being priced and why. Since we begin from forward money rates, money rates down the road are an expression of several critical factors, in many ways like bond yields. Growth and inflation are in there, but more so a determined nod to short run factors in the monetary system which get to those.

A 2008 crisis would definitely lead to depressed money rates far into the future, which is also consistent with very low growth and inflation expectations. Yet, there wouldn’t need to be an ’08 rerun to achieve the same thing, particularly in the aftermath of the original crisis. A sufficiently sizable disruption would do the trick, and that’s where the curves come in.

It’s like they’re describing the threshold for “sufficiently sizable.”

To show you what I mean, lets look at the second curve crash in 2011 – Euro$ #2.

We start out with the Euro$ curve relatively steep after the original Euro$ #1; though notice how it never got back to where it had been prior to the initial outbreak (on these charts I’m giving you peak to peak comparisons). That’s because the relatively flatter curve in 2009 was flattening already since many in the marketplace were increasingly worried the recovery wouldn’t go far enough in either the real economy or the monetary system.

As it would turn out, that was indeed correct and on both counts. We can argue about if the curve should’ve been even more depressed, flatter still, though already we have the outlines of the interpretation. Upward sloping isn’t really the issue, it is by how much!

By the time we get to February 2011, the Euro$ curve is even flatter though, again, still substantially upward sloping. The market wasn’t expecting rate hikes anytime soon, just that it hadn’t seen enough to get fully onboard with zero rates for the foreseeable long run. No one was thinking that way, at least not until the middle of 2011.

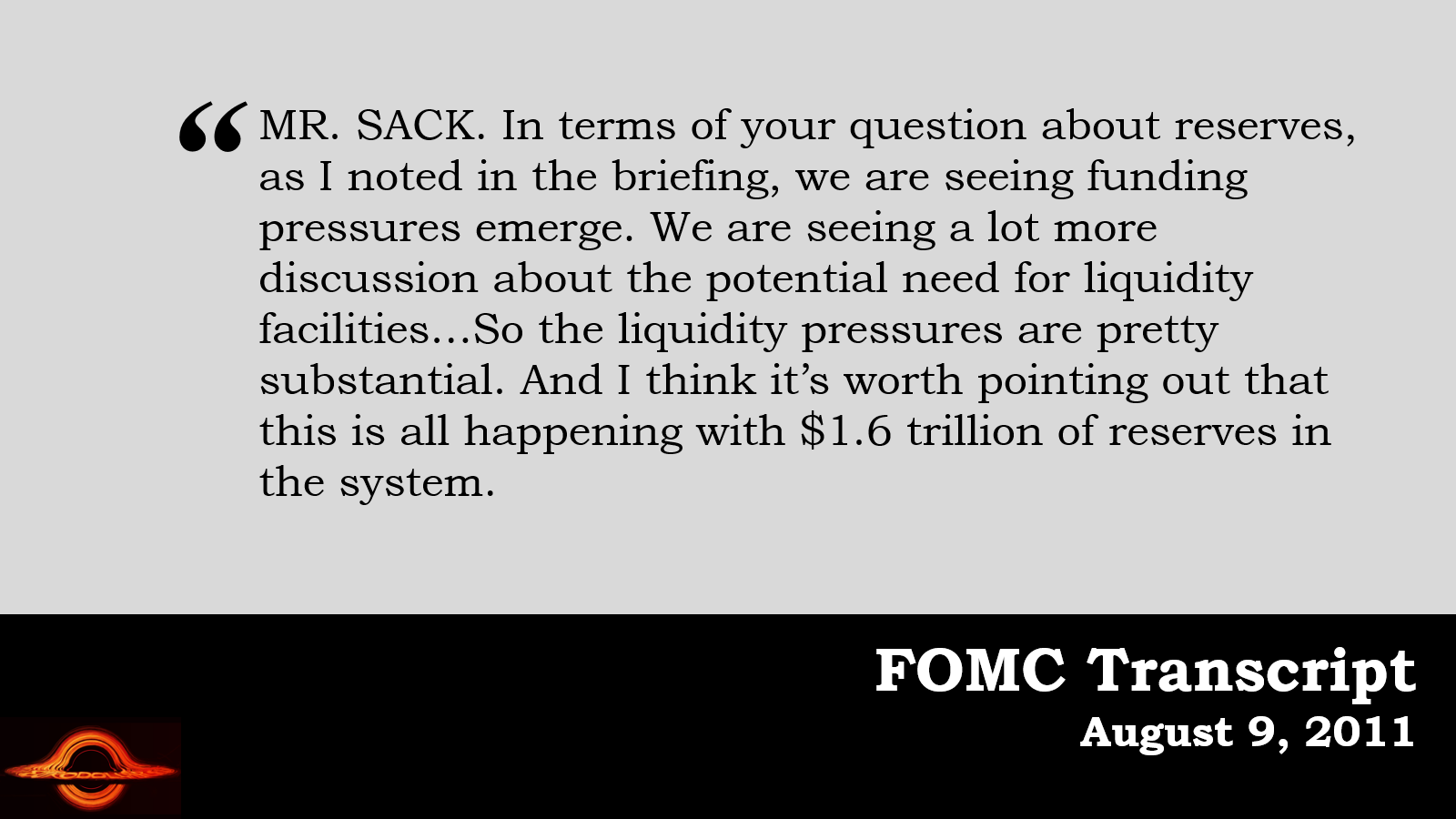

Look at how the curve utterly collapses in a matter of a few months (below). The liquidity crisis – in eurodollars – during them was pretty severe. Central bankers at the Fed were talking about having to try to bail out the system again, even after two QEs already and $1.6 trillion in reserves created by them (proof positive how little bank reserves matter).

Yet, no huge bank failures. Unlike just prior, millions of workers weren’t laid off. The stock market hiccup-ed rather than melted down.

Did the utter curve collapse in 2011 overstate the danger, then? Was eurodollars wrong?

Not at all.

What followed afterward was every bit as depressing as if those had repeated. In many ways, it was worse given that 2011 and Euro$ #2 was the final nail in the recovery’s coffin. After it, there was no coming back; the world had been put on that course by the more memorable events of ’08 but changed irreparably from ‘11 on.

And it was everywhere, not just the US. While the US would avoid an outright recession even in 2012 – another fact which seems to make suggest the Euro$ curve got it wrong in 2011 – many parts of the global economy did not, notably Europe. Worse, Asia and China showed thereafter they weren’t immune from the eurodollar disease which Euro$ #2 proved hadn’t been cured one bit.

That latter realization went a long way to explaining everything.

Given all those additional facts, even though the US didn’t suffer recession nor was there another Bear Stearns, the Euro$ curve absolutely got the crisis and especially its long-term ramifications as close to correct as humanly possible.

China is still slowing down to this day. Europe gets farther from its baseline with each passing quarter, the United States, too. Bonds yields everywhere went lower for years on end and wouldn’t see 2011 rates again until just recently, more than a decade later.

Eurodollar futures absolutely nailed Euro$ #2 even if it didn’t appear to live up to the eye-popping news cycles of 2008.

It would continue that way in the subsequent cycles, where the curve rose and fell with perceptions about reflation and further deterioration. During the latter, it steepened out somewhat though nowhere near embracing a recovery. When the former, more and more depressed even if the Federal Reserve was hellbent on raising ST rates anyway, such as 2018 into 2019.

The long run environment has matched the eurodollar futures market’s history even without a declared recession in America during any of it (2019 is debatable from before COVID, but we’ll never know).

It should be obvious why I bring this up, why I feel it necessary to conduct reviews like this (if in part because Todd prodded me for them). The eurodollar futures curve was nasty inverted before they went off the board for the final time this past April. SOFR’s curve is getting back to that shape.

Others like EurIBOR heading toward 2024 are even worse.

What are the chances of them signaling false positives? The better question, what is your definition of a false positive?

If you believe it is only about another 2008-like crisis, with more Lehmans and AIGs, then the chances of a set of false positives are pretty high. But that’s not what the curves are all about.

Instead, what they tell us is the likelihood interest rates can go higher and stay higher, or are they more likely to go lower and stay lower. During the eurodollar cycles over the last decade a half, the eurodollar curve was, indeed, largely correct each time as rates never really moved far at any point even during the rate hikes.

Not perfect, not 100% precise. Probability-wise, flattening curves panned out and even steepening reflation curves were accurate enough in the respect that there was never much steepening meaning the market was never assigning a high chance for reflation to become true recovery. Again, that was correct.

What these curves can’t or won’t tell us is how we get from here to there. They can give us a sense of what “there” most likely looks like, low rates and whatnot, it is still up to us and using other tools at our disposal to make some judgements about what can lead the world toward those specific sets of outcomes.

What our curves are saying right now is the opposite from higher rates and even higher for longer. Given ours and their history, and a more grounded view of it, dismissing them as false positives seems quite foolhardy. They’re not saying get yourselves ready for Lehman or even SVB. Those could be possible, but there are many other possibilities.

This includes what happened up to last year (did the curves get 2022 “wrong”?) and thus far up to this year. But that will have to wait for our next opportunity to review curve effectiveness.