THE ROOTS OF MORE UNITS

EDU DDA Oct. 30, 2024

Summary: A bunch of Q3 GDP data, including the US. Germany’s has displayed a plainly unnatural oscillation that opens the door to a much wider and more profound set of questions. Are their unit roots? If so, could these lead to difficulties in data masking the consequences in the real economy? The evidence does point in that direction with each major and minor revisions. Conclusively proof is elusive primarily because these series would be that proof.

There were GDP estimates all over the map today, meaning geographically dispersed not the results themselves. US real GDP missed expectations and slowed a little bit from last quarter, neither all that much or a big deal. European GDP bested what had been anticipated as a slowdown, accelerating a little during Q3 instead. Part of that was due to Germany which defied everyone posting a small positive rather than a second straight negative.

That meant for the German series, it has alternated between positives and negatives for ten straight quarters. I’ve never seen anything like it which raises the possibility of statistics. In reality, Germany is in a recession and a very bad one with no sign it is ready to escape, one that dates to a critical period in recent history, the middle part of 2020.

Full rundown on the stats can be found in today’s Daily Briefing, including a discussion about whether the bond market has changed its view of the near-term path for short-term interest rates (Fed regret).

Same goes for Europe. Though the numbers are accelerating there, the economy isn’t, not meaningfully and you can see the difference when plotting GDP in euros rather than by quarterly rates. This year’s pickup is a minor fluctuation, meaning the weakness which had become plainly evident is responsible for keeping GDP at these small rates whether plus or minus. There’s more trouble ahead, just like for Germany.

Is that pickup real, or trend bias?

The US situation is slightly more complicated and for much the same reason. When you see something like the German oscillation going back and forth perfectly interspersing positive with negative that’s not natural. In the same way the Establishment Survey has been revised lower the vast majority of months over the past two years, we’re picking up some biases in the various data sources.

To be clear, I’m not alleging conspiracies or anything like them. Governments aren’t cooking the books for whoever is in charge. And if they were, they’re clearly terrible at it. If they were going to cheat, you’d have to believe they would do so much of a better job and be more thorough and uniform (just rewrite the CPI down to zero, for example).

What I think has happened, a view shared in some circles, is that the pandemic has screwed up a number of accounts. These statistical numbers all depend on looking backward for guidance in how the “future” should unfold. It is the guiding principle behind trend-cycle assumptions, a widely acknowledged idea that an economy will only vary somewhat around a trend.

But that trend is unalterable. It might bend slightly but only over the ultra-long run.

The only change from that trend comes about during a cycle shift (why it’s called trend-cycle), meaning recession to recovery.

Milton Friedman’s plucking model for an economy is an apt summary of the…root concept. Though it never really caught on specifically, the idea behind it forms the basis of pretty much all economic thinking. Economies since the Great Depression don’t keep moving along only ever temporarily falling behind and even then catching right back up. As Friedman saw it:

Consider an elastic string stretched taut between two points on the underside of a rigid horizontal board and glued lightly to the board. Let the string be plucked at a number of points chosen more or less at random with a force that varies at random, and then held down at the lowest point reached…In this analogy, output is viewed as bumping along the ceiling of maximum feasible output except that every now and then it is plucked down by a cyclical contraction.

Statistical analysis and the construction of all our major macro accounts follow this line of thinking. The economy basically conforms to its prior trend, only suffering a short-run detour when confronted by a business cycle trough, a recession. Therefore, statisticians assign variations surrounding the presumed trend up until the time when there is overwhelming evidence the economy has been “shocked” away from that trend.

Even when that comes about, it’s still assumed only a matter of time before rejoining it – thus, recovery has a technical meaning.

The recovery itself is implied, thus the term “cycle.” Nothing is supposed to break that straight line potential, an assumption made because of the eurodollar’s history in between the Great Depression and 2008. But you can already see the common factor.

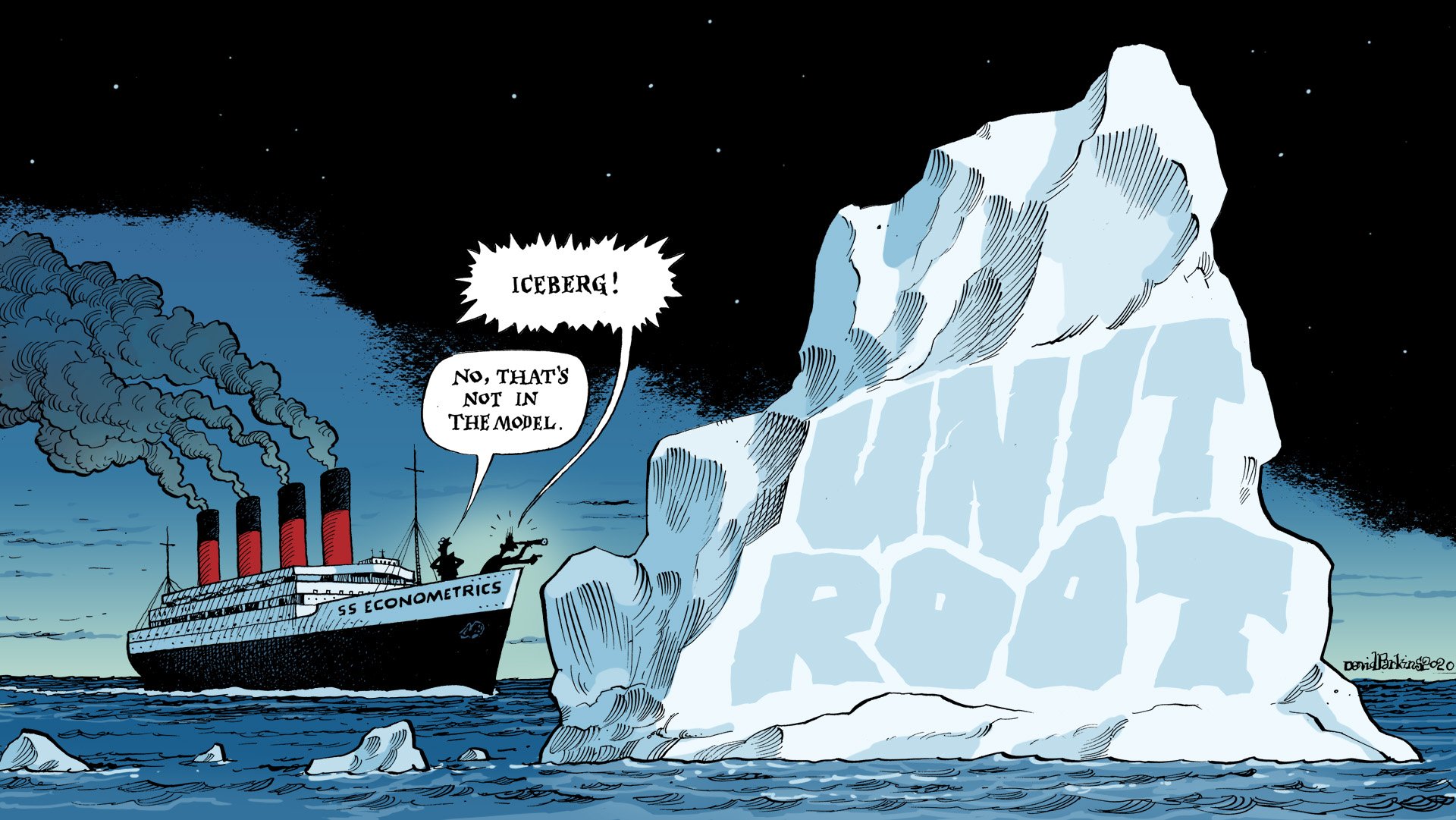

What broke down the trend into becoming the Great Depression? Same as what would starting in August 2007, if not to quite to equal degree. An enormous shock, then, might therefore lead to complete alternation in the trend itself. That would mean a unit root, not something Economists allow for mathematical reasons as much as legit economics (small “e”).

Unit root?

Technically, an equation that describes, say, a time series can be written out as a series of monomials. Each of these corresponds to a “root”, which, if it equals 1, means it is a “unit root.”

In econometric time series models, these things can be downright toxic – not a very good reason to hate them as Economists seem to. For variables like employment or even inflation, the presence of a unit root means the future would be completely unpredictable. Defined as a non-stationary process, or difference stationary, there would be no way of modeling the future based on the past because a unit root would lead to an entirely new future that wouldn’t revert predictably to a deterministic path.

Here's a stylized example using the simplest possible model with a single monomial, we’ll assume we are modeling an economy’s output gap. The time series equation can be given as:

V is the output gap at time period n, a function of C, the constant which we’ll set at zero (because the output gap is “supposed” to be zero), plus some value for a potential shock (causing the recession) then finally adding an error accounting for some minimal potential for randomness (which we’ll conveniently ignore here for the sake of simplicity).

All the equation really says is that when there is no shock the output gap is zero, therefore the economy behaves predictably as defined by its prior trend. But, if a shock is introduced, then the root highlighted in red comes into play. Any value less than 1 and this means the process is stationary or trend stationary – in that over time it converges to the prior trend (C) with an output gap of zero.

Below is what it looks like, and you can see that it appears as every postwar recession up until the Great not-Recession.

Even though the recession may not have been anticipated, the optimal output forecast would still be for a zero output gap. Over time, as Friedman’s plucking model, the shock shrinks back down to nothing and the economy gets back on trend. How much time it takes depends upon the root, in this case I’ve arbitrarily set it at 0.5. The closer to 1, the longer it would take for recovery (which implies other factors beyond our overly simplified model).

Stationary processes like these imply that any shock must by definition be a temporary one.

Watch what happens, though, if we set the root to exactly 1 – introducing a unit root into this simple equation. In fact, I call it the not-Recession because of what the real world evidence shows is inarguably a unit root:

A unit root here means that the process is non-stationary (or difference stationary) and therefore in terms of this very simple output gap model the shock in time period 6 couldn’t possibly have been temporary. A value of 1 or greater means a permanent change (aside, in statistical terms this would mean the entire statistical distribution has changed; mean, standard deviation, the whole works) that wouldn’t have been predictable given the limitations of the future presumably looking like the past.

If the non-stationary model introducing a unit root for our output gap looks familiar to you, it’s because it really should be:

Intuitively, however, Economists are generally right to point out how most variables wouldn’t appear to be able to come with one. The unemployment rate, for example, doesn’t just go up and stay high forever – there aren’t any cases in any time period where that might be a realistic possibility. In each and every business cycle, it leaps due to the recessionary shock and then comes back down. Why it might come down is another matter, another root.

Policymakers used to believe that it followed a stationary process pulled (mean reverting) toward its potential defined as “full employment.” While the unemployment rate itself obviously doesn’t have a unit root, perhaps the labor force like the output gap does – leaving the unemployment rate which discards this feature unreliable, mathematically unable to cope with what amounts to the participation problem in reality forbidden by econometrics.

To econometricians, this sort of thing should have been impossible. Even now, many perhaps most remain convinced there can be no unit roots in any of their models. Yet, evidence. Evidence. Evidence.

For what? Non-transitory economic shocks. That’s really what we are talking about in both worlds – the real and the statistical. A unit root again implies the possibility of permanent shocks (which could be good as well as bad).

Why is this disallowed?

Remember how statistics work: the math is limited to the past in order to project the future. A permanent shock violates this assumption because, by definition, it introduces some factor which must not have existed in the past; or, alternatively, in the chosen set of factors from which to begin modeling from that past. For econometricians, this is abhorrent.

Over here in the real world, hey, this is a dynamic place which is always changing in ways people in the past could never have conceived. And if you aren’t paying full attention to everything important about the past, then double bad on you. After all, we’ve seen them and it is foolish to believe they’ve somehow been solved or conquered in ways no one can seem to adequately explain (Ben Bernanke really tried the most).

The Great Collapse created an acceptable unit root because it was considered ancient economics and primitive money. Everyone believes – incorrectly – central banks and Economists figured everything out, especially during the Great “Moderation” to where something like depression could never happen again (Ben Bernanke even told Milton Friedman using those words).

Then it did (2008).

It caused enormous difficulties for statisticians on the other side of it, one reason why downward revisions became a defining feature in a lot of series (IP being my favorite to point out as the most blatant example). What’s happening is that the assumed pre-crisis trend is still valid therefore data sources are artificially biased to a higher trend which no longer applies; the unit root struck and altered that trend very similar to our stylized example above.

I think what we’re seeing across a lot of data is something similar, another permanent shock and a pretty intuitive and understandable one: the pandemic. A lot of things were upended in 2020 and 2021, perpetual changes to deeply fundamental factors. Small businesses that were artificially shuttered never to open. Business that would have gone to those instead rerouted by government to big corporations who pocketed the price illusion. So many such artificial distortions, it’s wild how so many assume those wouldn’t have created permanent shifts, a lot of potentially really harmful examples (how about this one: governments using the pandemic accidentally discovered how they can borrow carte blanche).

Unlike after 2008, the statisticians are not handling it the same way, constantly estimating and even revising data in various ways at shorter and longer-term intervals (like benchmarks). I think the German GDP series is an example of the former, while US GDP may be one for the latter.

Look at how GDP has changed over the last four benchmarks, though this is something of a no-no, comparing series with 2012 $s to the later ones denominated in 2017 $s, for our purposes, you see what looks like data that “wants” to display a post-2020 unit root the BEA, in this case, instead keeps trying to revise out.

GDP seems to literally seek the 2010s baseline. And it isn’t the only series; the same agency did this with income stats, too, especially DPI and to a lesser extent Real Personal Income ex Transfers.

The price illusion in 2021 is a part of this mess. It started out like a system that was indeed attempting to return to trend – a recovery, a “red hot” one which appeared at first to be legit.

This only pushed the appearance of the unit root out a little further in time, the downside of the supply shock emerging in 2022. That’s why we keep seeing this all over the place, including European/German GDP and also, previously, a big deviation in the US data. That was the “technical recession” which created a choice for statisticians.

They could either allow the post-2022 data to continue showing the break in trend, believing that 2021 was a false recovery after a unit root. Or, they could look at 2022 as being the false break from recovery and since they don’t believe a unit root is possible that seemed the more valid assumption therefore constantly trying to upward bias data so as to get back on to recovery.

Even to the point they “discovered” massive and previously missing GDP and income.

DPI is the clearest example of these post-2022 changes.

It is certainly possible that the BEA or whichever other agency tinkering with whatever data series and survey results “found” a ton more income and economy (in real terms, too) than had previously been figured, and that’s what accounts for massive revisions. While I can’t dismiss the possibility, I’m more inclined to believe 2020 was indeed another permanent shock, 2021 was the false signal, and naturally all of it creates major difficulties.

To me, this makes a lot more sense and aligns far better with outside observations (starting with what markets are pricing).

Payrolls, anyone? Why else do we keep seeing revisions in those not to mention the “middle finger” months that appear out of nowhere (like September) whose sole purpose quite blatantly appears to be maintaining a predetermined trend that isn’t found in other sources less statistically overburdened.

We already see another unit root clearly in labor participation, the big one, which would be a reflection of the same in the economy and contribute to the same permanent change across incomes.

This doesn’t mean the latest GDP estimates for Q3 2024 in any one of these places is “covering up” some huge contraction consistent with a full-blown recession of the kind everyone would immediately recognize. It’s even more profound than something like that.

This matter isn’t really about recession risk or recession at all. It’s more an issue for an uncertain long run to which a potential recession might play some part. US GDP hugging the 2010s baseline like it does now appears artificial and inconsistent. It is the choice of believing 2021 when almost everything this side of 2022 is leaning, or would if allowed, toward a 2020 unit root.

And to me, recession would be, or is, part of the process finally exposing it.