INDIA PREMIUM

EDU DDA Jan. 31, 2025

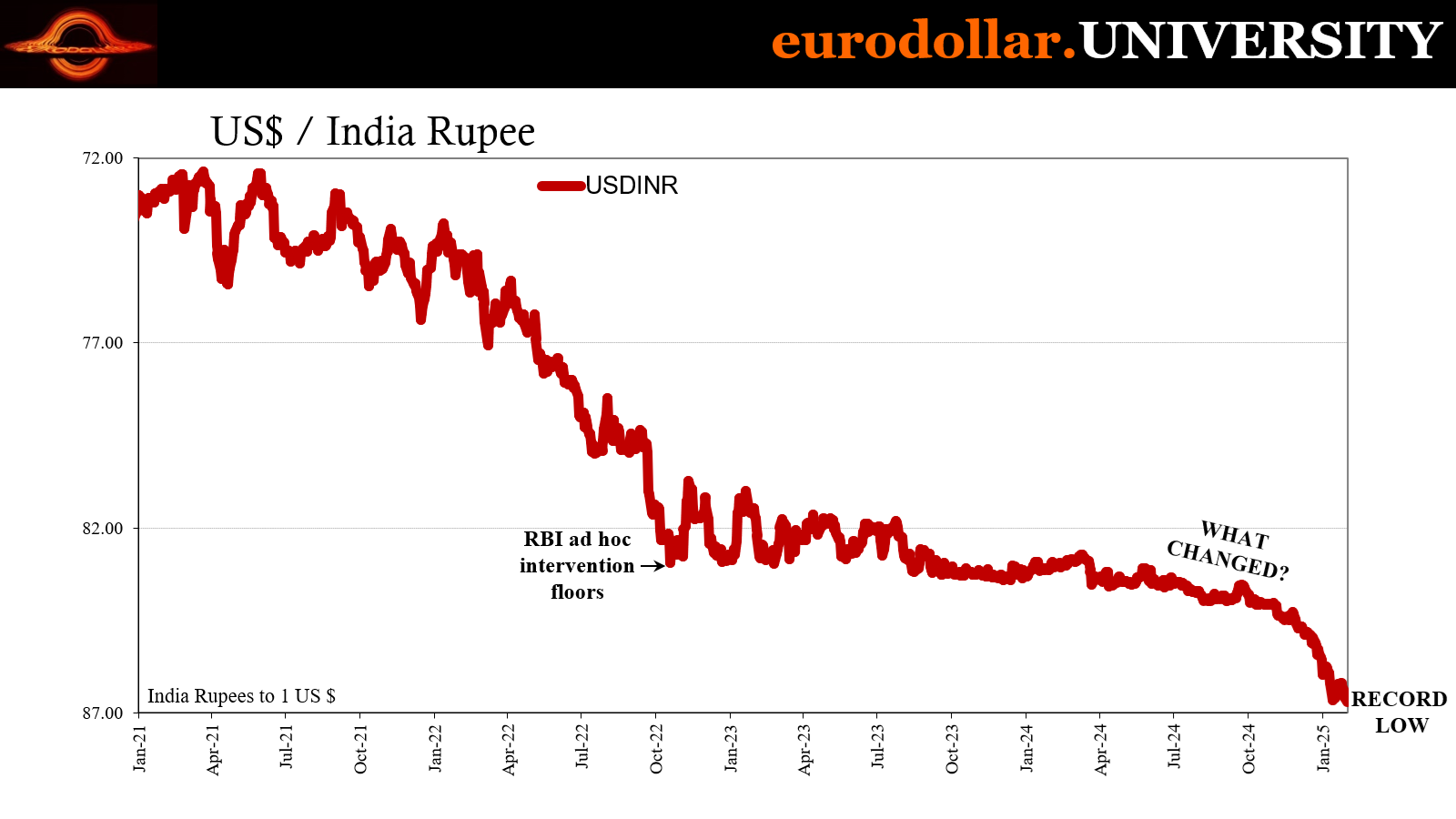

Summary: India’s banking situation has gotten to be a disorderly mess. RBI has had to initiate swaps, TOMOs, repo auctions, what they even called a “bazooka” to calm things down. Where did all this come from? Consequences from the eurodollar premium. According to the latest indications from it, such as primary dealers hoarding another massive record high in Treasury assets and very low yields on Japanese bills, this latest disruption isn’t yet done. The dollar has lost some of its urgency on trade wars fluctuations, not its background premium.

India’s foolish effort to the alleviate its dollar problem has left its banking system facing a growing monetary shortfall the central bank is having quite a lot of trouble containing. The negative impacts only go on from there. This isn’t going to get any easier given the latest indications from the eurodollar, starting with another record high in dealer holdings of Treasury notes and bonds to go with unusually low bill rates – T-bills and J-bills.

If this Indian plight sounds somewhat familiar, it should; the Chinese system was dealing with something similar, and, to some extent, for the same reasons. Basically, government interference comes with costs, sometimes sizable unintended collateral consequences.

For China, balance sheet-constrained dealer banks have been constantly tapped to rescue the yuan. Borrowing dollars in FX markets, they relend the proceeds locally, onshore as well as, at times, offshore (Hong Kong). Having “bought” yuan with the dollars they “sold”, that can leave less available in the marketplace since that yuan also doubles as collateral for the dollar borrowings.

The Reserve Bank of India takes care of the currency exchange matters on its own, which just guarantees to lock up any rupees RBI takes in. Since the central bank has been intervening by an enormous amount the past few months, local liquidity has suffered for it. Like China, the combination of FX sucking up spare funds along with some idiosyncratic seasonal matters (tax payments in India, the Golden Week in China) has created a growing mess in both places.

China’s has mostly calmed down. According to external assessments, the Indian banking system hasn’t experienced this much of virtual cash shortfall in over a decade.

To address it, RBI has been buying government bonds – open market operations that temporarily raise the level of reserves available for banks. The latter sell their bonds and receive a form of interbank token (reserves) in return which can be used for settling transfers between themselves and others, or back to the central bank for when tax payments get made.

It isn’t actual cash, a lesser for of limited use ledger credit.

On Monday, the Reserve Bank took in 600 billion rupees in bonds and then supplemented that action with a $5 billion swap (held today), its first use of that tactic in half a decade going back to the pandemic crisis. On top of those, RBI then announced an additional 56-day funding (repo) auction to be held on February 7.

And it still wasn’t enough to quell the cash crunch.

Altogether, those with additional measures were even advertised as an $18 billion, oh boy, bazooka (not my term). Unlike currency interventions which are meant to stabilize the sliding INR exchange value by buying rupees from the foreign currency market, these other currency swaps do the opposite. Instead of RBI “selling” rupees to “buy” dollars as it does when trying to steady the rupee, this other kind is done mainly with local banks not the FX market, therefore providing specifically Indian banks with rupee cash they can then relend into the domestic money market.

Demonstrating just how messed up the situation has become, that initial $5 billion FX auction tranche was oversubscribed by a whopping five times, taking in a reported $25.6 billion in bids.

And then, over the past two days, RBI bought another 200 billion in bonds during more open market operations, followed by another announced repo auction.

The proximate cause was, again, dollar tightness from the end of November forcing the rupee even lower and RBI to abandon some or most of its previous forex interventions likely at large losses. There are still more of those which will need to be unwound in the months ahead given how the last round of heavy FX interventions came with three- and six-month terms.

Therefore, a lot of rupees remain locked up in RBI’s FX “pool” which can’t be otherwise accessed, having been effectively taken out of the local system for, what? INR has stabilized over the past several weeks no thanks to anything RBI had done. Instead, the temporarily receding prospect for “trade wars” opened up a window for calming the global dollar down, sapping some of the urgency which had driven a near-crisis in November and on through December.

While the emotions of “trade wars” may have now swung back the other way to an extent, like JPY and CNY, the background dollar tightness remains there anyway. To start with, FRBNY’s reported custody of foreign official Treasury reserve assets has only partly rebounded despite the reprieve.

The timing lines up exactly on both ends: while the dollar was slamming higher since November 26 or 27, more than $80 billion of Treasury holdings got used in some fashion. This was an enormous amount, on par with some of the past few years’ biggest dollar shortages, including March 2020.

Treasuries came trickling back in starting the week of January 15, right when the dollar exchange value slacked off. As of the latest weekly update, the balance remains $30 billion shy of the November 27 level and $40 billion below the first week in November.

Another critical tightness indicator, primary dealers’ inventories of Treasury coupons continue to soar even here in the second half of January. While some slack has appeared in the eurodollar flow, those dealers aren’t behaving like they see the prior tightness as a one-and-done matter. Their hoarding went nuclear starting that final week in November, soaring by an enormous $69.0 billion between then and the end of the year.

In January, they added another $19.7 billion bringing the total to $284 billion, a new all-time high. That’s nearly $50 billion more than what primary dealers were hoarding at the peak during the August carry trade meltdown. They were, and still are, bracing for more dollar disruption.

And speaking of the Japanese, we’re getting indications of heightened demand for bills on both sides of the yen/dollar redistribution. Starting with T-bills, yields for them had been relatively tame since the start of the outbreak in early December when auction demand skyrocketed.

After then, the 4-week bill rate had been stable from mid-December right on through to the past few days. The 4w rate dropped six basis points yesterday for otherwise no apparent good reason. The 3-month bill had slipped lower at the start of this week, by a few basis points and now closing in on the lower end of the fed funds range (which indicates heightened demand, particularly in the absence of more immediate cuts to the range).

Over on the opposite side, Japanese bills have been under relatively constant demand throughout this episode. Looking first at the 3-month J-bill, it had been absurdly low, of course, the entire carry trade mess and then beyond as it extended well into September if in the background. In early November, however, the rate started to rise either as normalization - lessened demand for collateral - or simply in anticipation of the next BoJ rate hike which could have come as early as the December meeting (officials instead opted to hold until last week).

Whatever the case, that rise was abruptly interrupted Thanksgiving week in the US, even before we got to the dollar slam (we did see primary dealers stack some coupons and a lot of bills at that time, however). The 3-month rate would then stick around the 13-bps level, well below the then-existing O/N policy rate of 25 bps, let alone the upcoming 50 bps where it is now.

It wasn’t until the final week in December that it finally pushed higher again, the growing expectation for the January rate hike overcoming any collateral demands. The rate got up to the high 30s right before the BoJ last Friday, but then slid lower this week despite never coming close to the policy rate.

Whenever we find something like a bill yield that is so far below an alternative rate, that strongly implies extraordinary need to use the instrument as collateral; in the case of Japanese bills, as an alternative to dollar collateral up to and including a potential scarcity in Treasuries. Quite simply and intuitively, if the marketplace is willing to give up that much additional return, what other possibility is there?

For the 3- and even 6-month J-bill, right now holders are willingly taking around 32 or 34 bps (respectively) in yield when they could instead lend their yen in repo at approximately twenty basis points more. And in a low-yield environment like there is over there, leaving twenty basis points on the table is an exceptionally high opportunity cost – unless the lower-yielding security yields some other value apart from its investment return.

Collateral.

Like US primary dealers still hoarding inventories this late in January, the low yields on these J-bills signify the dollar difficulties of the previous months aren’t done. There may be less urgency without the immediate strain of possible “trade wars” – though that possibility reignited today with the Trump administration stating additional duties on China, Mexico, and Canada are indeed going live tomorrow as previously specified.

Maybe that’s why dealers didn’t give back any of their bond stash, and demand for J-bills remained tight – an expectation that eventually tariffs were coming no matter what or how it might have looked at various points on the way to them.

I still believe this goes way beyond trade “frictions.” As detailed in yesterday’s DDA, all of this, the whole ballgame, traces back to the inflection points around the end of 2022 and the start of 2023; the “gilt crisis” then the “banking crisis.” These are longer run problems that have created stresses on the monetary system adding more difficulties to the struggling real economy while simultaneously reflecting them.

In fact, you can also easily see that where it comes to Japan. The correlation between Japan’s yen exchange value and long-term bond differentials was exceptionally strong in 2022 and part of 2023 before not quite breaking down, being supplanted after the bank crisis inflection with “another” factor.

As I wrote in today’s Daily Briefing when examining specifically the yen here:

While the relationship between the 10-year differentials and JPY is still there, as you can see below that doesn’t explain the degree of yen weakness the past few years, only some of the variations in it along the way.

That other factor is the eurodollar premium. Seeing it develop so strongly from the end of 2023, the aftermath of the initial leg to the bond rally (i.e.; growing demand for safety and liquidity), like the bank data or just curve changes the past few years this is another more visible sign of global fundamental influence that long predates the idea of trade wars.

This eurodollar premium simply denotes risk aversion and relative tightness in financial conditions across the dollar world – the kind which might convince primary dealers to increase their holdings of Treasuries either as a defensive measure (protecting against what could be costly collateral shortfalls) or to take advantage (selling or renting those Treasuries at higher prices or rates) of further breakdowns tightness might trigger.

The same tightness which, if gone too far, would lead foreign officials to have to sell or otherwise pledge tens of billions of their own reserve Treasuries, disappearing them from custody with the Fed in New York.

That eurodollar premium still visible with the yen is also there pressuring the rupee, forcing RBI to try to counteract the shortfalls that come with it by costly interventions which create very real consequences internally for all that external disorder.

India’s participation in that doesn’t come in a vacuum. INR has historically shown itself to be highly sensitive to these mechanisms of eurodollar difficulties, including a correlation with dealer holdings. Where it comes to 2024 and now 2025, this time around it’s the same local macro story which gets mixed up in the global cycle.

Just this week, the Indian government reported it now expects economic growth to fall substantially short of the prime minister’s target Mr. Modi set out to transform the economy into a developed one. These latest estimates, released today, are even worse than the preliminary numbers offered a few weeks ago.

One key reason why, here comes more signs that the currency and liquidity issues are just now beginning show up hampering the real economy. As Bloomberg reports today:

After two years of calm, the rupee’s sudden slide is starting to strain Indian corporate earnings, sparking a rush among some companies to hedge their currency exposures.

InterGlobe Aviation Ltd., which runs India’s largest airline, saw its foreign-exchange losses jump threefold to 14.6 billion rupees ($169 million) in the December quarter. Adani group’s flagship Adani Enterprises Ltd. on Thursday reported a sharp fall in profit, citing foreign exchange losses.

Now, with economic growth slowing and global volatility rising, companies find themselves strained to hedge their exposures just as rupee declines are expected to deepen.

Higher “hedging” costs are just another expression of the eurodollar premium making economic and financial life more difficult.

Rather than the 8% level of the past few years, given the whole range of monetary and global economic “headwinds” Delhi now hopes for something like 6.3% to maybe 6.8% GDP growth for the upcoming year beginning April 1. With that comes a whole range of risks, including an imbalanced banking system which expanded greatly on the promise of 8%.

Weak internal fundamentals combined with too many growing external headwinds leading to a rising eurodollar premium and shortfall of dependable global funding that blows back on the Indian banking system for the central bank’s attempt to at least limit the downside which, in failing to achieve that goal, is now really causing even more visible harm in every one of these capacities.

This dollar stuff can seem esoteric and ephemeral, yet there are very real consequences even if it takes some addition effort to smoke them out and put the pieces together. No wonder gold’s at a record high and driving copper-to-gold even lower still.