JUST CALL IT STEEPENING

EDU DDA Nov. 1, 2024

Summary: Payrolls were ugly in October and that wasn’t the only problem nor the worst part. Despite what sure looks like recession in the jobs market, the long end of the yield curve keeps selling off, rates rising when it seems like they should be doing just the opposite. The short end is, with bill rates more aggressively going lower as, at the very least, the next set of Fed rate cuts is basically locked in at this point. How, then, do we explain this odd curve divergence? The answer is that there is nothing odd about this at all.

Whoever it was that bid up the 4-week bill yesterday got it exactly right. At least, as I wrote in yesterday’s DDA, there were several carry-trade steps which seemed to be anticipating a bad payroll number, the effect of which created conditions that shoved the 4w yield down a whopping 11-bps a full day prior to the BLS release this morning.

Some of that definitely seems collateral-related therefore Japan, though I believe a fair amount of yesterday and today in most of the bills, not just the 4w, was also price an even higher chance of the next two Fed cuts, starting next week and then again in December (25s each).

Whatever the reason for the big bill trading, the object of it lived up to the hype, unfortunately. The BLS’s labor estimates for October were grim well beyond any impact from hurricanes and Boeing’s mismanagement. In fact, the big takeaway wasn’t even October. Revisions to prior months completely flipped the picture – it had looked like some weakness in employment heading into summer that the whole economy bounced off of exiting into fall.

That’s what made the September payroll seem (slightly) more credible since August had bounced higher first from July’s shock low; at least it had before today’s revisions. The BLS instead massively reduced (-60k) August down below 100k, worse than the original figure for July, the one that set everything off in the first place. Moreover, private payrolls were revised down to just 37k which means they were almost certainly negative.

And that was August.

Just imagine had these numbers been reported two months ago in early September. It completely changes the narrative from September payrolls being confirmation of a bounce right toward soft landing to a clear summer stumble which leaves September as the obviously outlier. October with or without the hurricane/strike effect would’ve been weak enough anyway to just continue the same trend.

Payrolls are now firmly on the side of everything else from JOLTS to nominal incomes, all of it well within the danger zone and maybe recession itself (depending on how much more revisions to payrolls there will have to be).

For a completely breakdown of both the October CES and CPS, including another drop in the latter with no detectable impact from the storms, here’s today’s Daily Briefing (also includes an ugly ISM and its employment index doing the same thing). I’m also going to cover the various angles to the payroll reports tomorrow on YT.

Today’s DDA is instead going to investigate what has puzzled quite a lot of people, including many who actually do understand bonds. With recession being more and more confirmed here, the short end is doing just what you’d expect given those odds. The long end is obviously doing something else.

Trading after the payroll numbers came out perfectly illustrates this, well, conundrum. Just prior to the release, the 10-year UST had sold off a touch backing the yield up to 4.317%, right at the top of the range from recent days. When the number came out at 8:30am ET, at just 12,000 it was well below expectations refuting September just by the headline (the details were even worse).

Straight away, buying came into the 10s like you would expect, pushing the rate down to 4.231% and everything seeming to be on track. It didn’t even last a half hour, though, as just before 9am the selling came in and didn’t let up the rest of the day. Even when the ISM came out at 10am ET, the market reversal didn’t let up.

By the end of the day, the 10s had soared nearly 11 bps above Thursday’s close. At the same time, the bills did the opposite, including the 4w which shed another bp and the 3m which moved down three more on top of three yesterday. The curve is moving in opposite directions quite aggressively.

The one part is easy. Bills are dropping because the economy is heading toward recession, if it isn’t there already, and that means rate cuts. They are all but guaranteed in the short run after today, next week and December basically locked in. Even if the US isn’t in recession or policymakers still not realizing this, the payroll evidence, especially combined with everything else, is more than enough to keep the FOMC reducing rates in the near term just out of caution.

Why wouldn’t that do the same to the long end?

The idea of a “Trump trade” has been gaining over the last month or so. Some may believe that with chances of his re-election (technically) rising either that means better policies or at the very least a vastly different approach on the fiscal side (tax cuts and tariffs) than what is clearly not working right now. Like 2008 when Obama bested McCain, there was some thought that it didn’t matter what Obama might propose since he was represented a total changeover from Bush when it was plainly obvious nothing was going right under the latter.

I’m not here to argue the merits of the election or the possible policies introduced (or not) by either side. There is at least some logical sense to the notion on the narrow grounds of market behavior and it could explain trading today. If you think Trump is different and different is good, then the dismal payroll report might be seen as boosting Trump’s chances at this last minute therefore the long end selling off (higher growth and inflation over the long run) after the initial brief rally.

There probably is some of that thinking animating more than a few market participants, though more likely in the short run than any other timeframe. However, looking at this seeming dichotomy between bills and notes/bonds, I don’t believe it is Trump, Harris, Biden, or anyone else in the political realm.

I’m also (regretfully) discounting the possibility from the “other” side, the one which sees Trump’s election chances as bond market negative (which seems to be everyone at Bloomberg). This other “Trump trade” says his election would mean more fiscal deficits, therefore higher inflation and more debt. But bonds aren’t suddenly going to begin worrying about deficits now after the last four years, especially the past two when there wasn’t even a pandemic to at least provide some justification for the out-of-control spending and borrowing. Why would bondholders suddenly revolt now after all that?

As far as inflation, remember massive government borrowing is far more likely to contribute to disinflation even deflation by being a consistent artificial drag on growth potential – bond market positive, more demand for safety and liquidity. The debt “paradox.”

Besides, the fundamentals for interest rates consistently in other places and markets continue to strenuously argue for all of them going lower and staying there over the intermediate and longer run. Quite simply, that means the Treasury market isn’t for or against Trump or Harris, rather the curve is just steepening.

This isn’t some unique puzzle. It is, in fact, quite common.

I recently covered what happens to long run interest rates like the 10s USTs after Fed rate cuts. This is a slightly different angle from that, covering the process from the perspective of bills going one way when the longer-dated notes or bonds go the other like they’re doing right now.

And there are loads of examples, before and during recession cycles. To limit our review, we’ll just go over a few from the 1990-91 cycle forward.

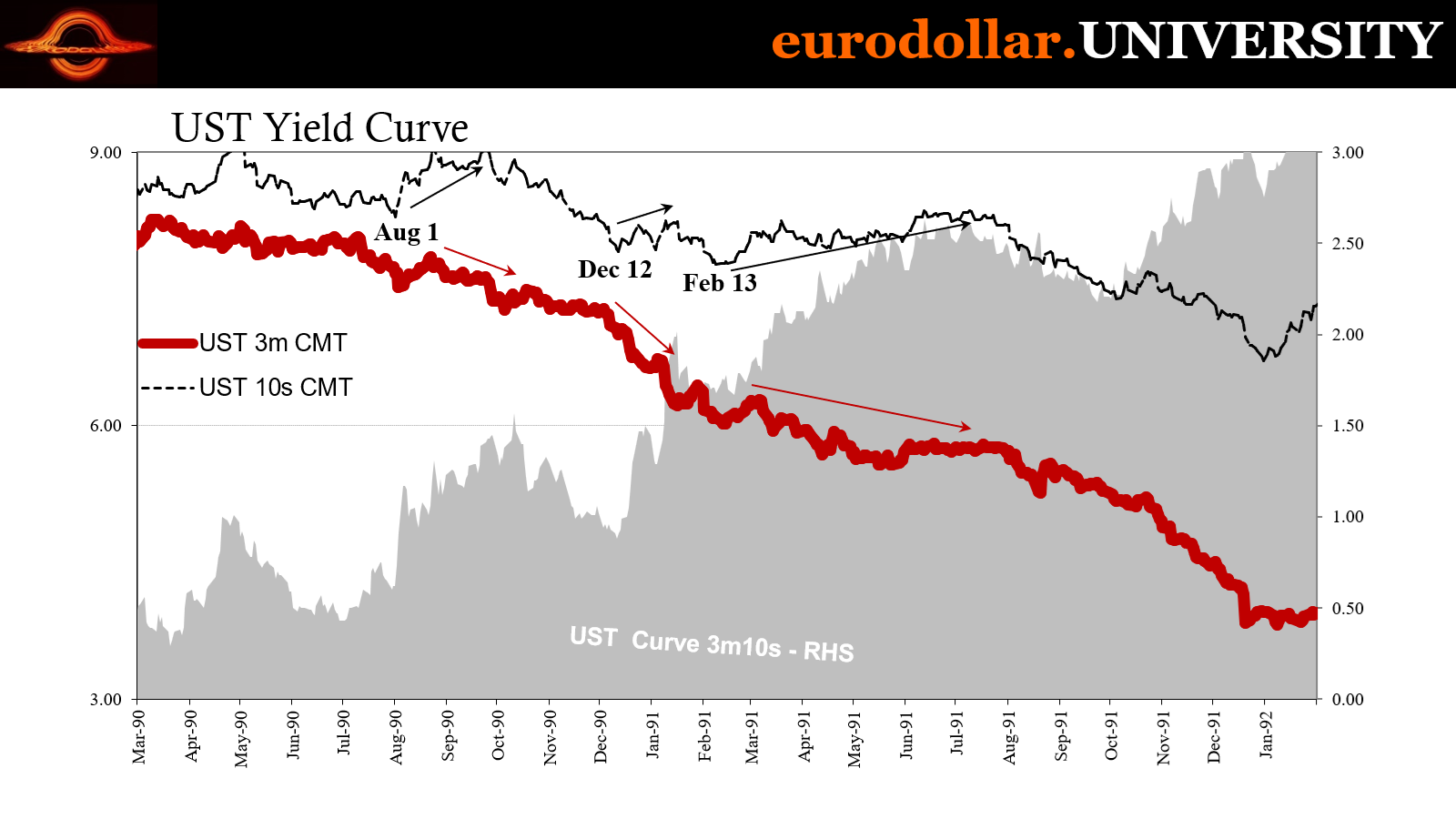

Following the initial Fed cut in July 1990, the 10s backed up through August as it looked like the economy might avoid a full-blown contraction; strong and resilient, early 90s style. From August 22, the 3-month bill went the other way, steepening the yield curve more than it had been before August. The 10s eventually backed up a sharp 75 bps (today’s move is hardly unprecedented) through mid-September at the same time the 3m bill ended up going lower by about 20 bps with more signs of recession stacking up, not to mention likely further rate cuts from Alan Greenspan.

A clearer example followed later in 1990 when the 3-month rate plunged as the recession deepened and the Fed began to act more aggressively (not that it would do any good). The 10s had moved down to 7.91% by December 12 and then sold off from there in spite of deteriorating macro conditions, reaching 8.25% in early January 1991. While that doesn’t sound like much, at the same time the 3m bill had crashed from 7.06% to 6.40% and then kept on going lower from there (with the 10s joining after all that steepening first).

Finally, from mid-February 1991, the 10-year would rise again as the S&L recession finally drew to a close. But the rates cuts, therefore lower bill rates, were not over because the recovery following it remained unusually weak and extended another year and half into 1992. During that initial phase, the 10s would go up from 7.70% to 8.35% when the 3m bill dropped from around 6.10% to 6.20% down to the 5.70s% further steepening the curve as fundamentals didn’t improve nearly enough.

The dot-com cycle featured a couple of additional examples, including what may be the more suitable of the entire lot. First, the short run right from January 2001 when the 3m bill dropped sharply and un-inverted what had been an inverted curve before then. It would go from around 5.90% to just above 5.00% in a month while the 10s initially fell under 5.00% then moved up to 5.34%.

At that time, the dot-com recession hadn’t yet (officially) begun.

The example after that is, I think, the clearest and more similar case. The 3-month bill had been falling fast from before March (just like before the middle of September 2024) in tandem with the 10s. The latter had dropped down to 4.73% by the 22nd while the bill was speeding lower to around 4.25% from 5.00% just a month before.

Following March 22 and going forward, the 10s turned around and sold off for two solid months, the yield retracing all the way to 5.54% by the end of May 2001. During those same two months, the 3-month bill crashed to just 3.63%, a truly massive divergence – steepening - between the yield curve’s front end and the back.

It was +81 bps for the 10s versus -55 bps for the 3m.

Was the long end completely ditching the recession? Not at all; the contraction was still getting started right then, officially beginning in the same month, March, that this curve separation amplified. That initial beginning phase, however, didn’t quite look full-on recession with mass layoffs only getting started around June – right when the long end then moved to converge with the short end.

There was another separation later in 2001, very similar to the final one for the S&L cycle coming right at the end. Heading into 2002, the official contraction was over as was the worst part, but the recovery following was minimal at best. That meant more rate cuts from the Fed so ST bills went lower when initially the 10s were shifting toward recovery mode; only for the latter to turn around in early 2002.

There were a couple examples in 2008, starting a run that has weirdly yet consistently focused on September and October. The first of those, September/October 2007, was the familiar one we’re seeing now, from before the official recession start when there was a higher degree of ambiguity and uncertainty. The later example was more of a unique case during the thick of the worldwide panic, so even though the front and back of the yield curve went in different directions, the reasons why were not equivalent to our current situation.

I’ll also briefly mention 2019’s example for the few similarities. The 10s had fallen up until early September then – in volatile fashion, given repo – went higher for nearly the remainder of the year while the 3m bill would go lower during the second half of September then continue gently downward throughout the rest of 2019.

Whether that was another curve diverge at the start of a recession we’ll never know. It is interesting how this took place yet again in September/October. Not just 2007 and 2008, also 2019 and here again in 2024.

So, again, I don’t really believe the separation on the yield curve front to back have anything to do with Trump or politics one way or the other. It seems far more likely – and I mean not even close – this is simply just the way the market behaves at these times, volatility, fluctuation and, to some degree, ambiguity. In fact, during these periods we might better follow the front end rather than the back at least as far as recession goes.

The October payroll report was another soft-landing killer, more importantly showing major weakness over the summer leading up to now. That means lower interest rates in the short run, which is bills, and eventually the long run, where swaps are pointing. It all continues to line up, sadly.

Eventually, the long end will come back to it after the curve steepens out somewhat first. It is, after all, called bull steepening for a reason. Part of that means more buying interest in the front than at the back, the common theme in all these examples.

In other words, it isn’t so much a selloff as that steepening and it is just as much consistent with recession cases even if the divergence doesn’t look or feel like it. At first.