DO WE REALLY NEED THE BANK OF CANADA?

EDU DDA Oct. 16, 2024

Summary: Canada’s CPI becomes the latest to drop into the “undershoot” category raising the dangers of becoming the “bad” kind of disinflation. Economists in the country are already calling for a more aggressive response. But who should it be who does respond? This sounds like an absurd question since Canada’s weakness is the Bank of Canada’s territory. The evidence instead importantly shows it doesn’t matter what the BoC does. On the contrary, bad disinflation in Canada is actually everyone’s problem.

Canada reported a sharply lower annual CPI rate for September, one that is almost certain to convince policymakers at the Bank of Canada to cut at double their previous pace at next week’s policy meeting. What we are seeing from the “Canadian economy” applies as much to everywhere else outside of Canada as it does in further confirming it doesn’t matter one bit what the BoC does today, yesterday, or tomorrow except their response to these price changes is just one more thing saying the same thing.

It is taken for a given by most mainstream characterizations that national economies are, well, national. They almost have to be inside those worldviews otherwise they all far apart, particularly their prescriptions for what should be done when something goes wrong. Paul Krugman, for example, is a perfect example of both the idea and its limitations.

Krugman had offered a simple four-part summation of neo-Keynesianism around a decade ago. In the middle of the 2010s, after so much had gone wrong since 2007 and little afterward going right, criticisms of the policies implemented during that timeframe were understandably everywhere. Writing in The New York Times, as usual, the Nobel prize winner quite helpfully condensed the theory into a quartet of bullets:

1. Economies sometimes produce much less than they could, and employ many fewer workers than they should, because there just isn’t enough spending. Such episodes can happen for a variety of reasons; the question is how to respond.

2. There are normally forces that tend to push the economy back toward full employment. But they work slowly; a hands-off policy toward depressed economies means accepting a long, unnecessary period of pain.

3. It is often possible to drastically shorten this period of pain and greatly reduce the human and financial losses by “printing money”, using the central bank’s power of currency creation to push interest rates down.

4. Sometimes, however, monetary policy loses its effectiveness, especially when rates are close to zero. In that case temporary deficit spending can provide a useful boost. And conversely, fiscal austerity in a depressed economy imposes large economic losses.

These all sound reasonable in the sense each one appears to be consistent. We can – and will – argue about correctness, the terms of all four points are clear and easily understood. At the root of the matter, faced with a downturn Keynesians believe a central bank should lower interest rates through any means and when confronting the nominal limit of zero the fiscal authority should step in to supplement the “stimulus.”

It is very much along the lines of what the Chinese are thinking about currently. Though the PBOC and market rates are still moderately positive, they are low by historical standards and creeping downward all the time after going only in the one direction (which should be a clue, but this deficiency is never addressed).

No one ever stops to ask, faced with material weakness exactly which authority should be the one responsible. And I don’t mean monetary or fiscal, I mean which monetary or which fiscal.

It may sound absurd; if the US economy is experiencing a rough spot, who else would we be talking about? This could only mean the Federal Reserve and Uncle Sam. The American economy is American so the responsibility of American officials in one capacity or the other.

Setting aside this annoying and even destructive fetish for all things centralized and official, what about, say, Canada? Again, mainstream thought says Canadian weakness needs to be addressed by Canadians because the economy is entirely of and for Canada.

Is it really?

These specific thoughts were vexing Dr. Krugman at the time he wrote the above. Criticisms were coming at him from all over in particular for applying those principles to the Japanese situation. He had advised Tokyo and former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe as the latter formed what became known as Abenomics. It was essentially the latter two on Krugman’s list put on steroids.

It never worked, a fact which had become clear enough by late 2015, two years into the QQE debacle.

Never once prior to 2016 did he or anyone in Japan ponder whether or not the Bank of Japan or the Japanese government were the right tools to fix the Japanese economy. It’s all just taken for granted national economies are what they appear to be.

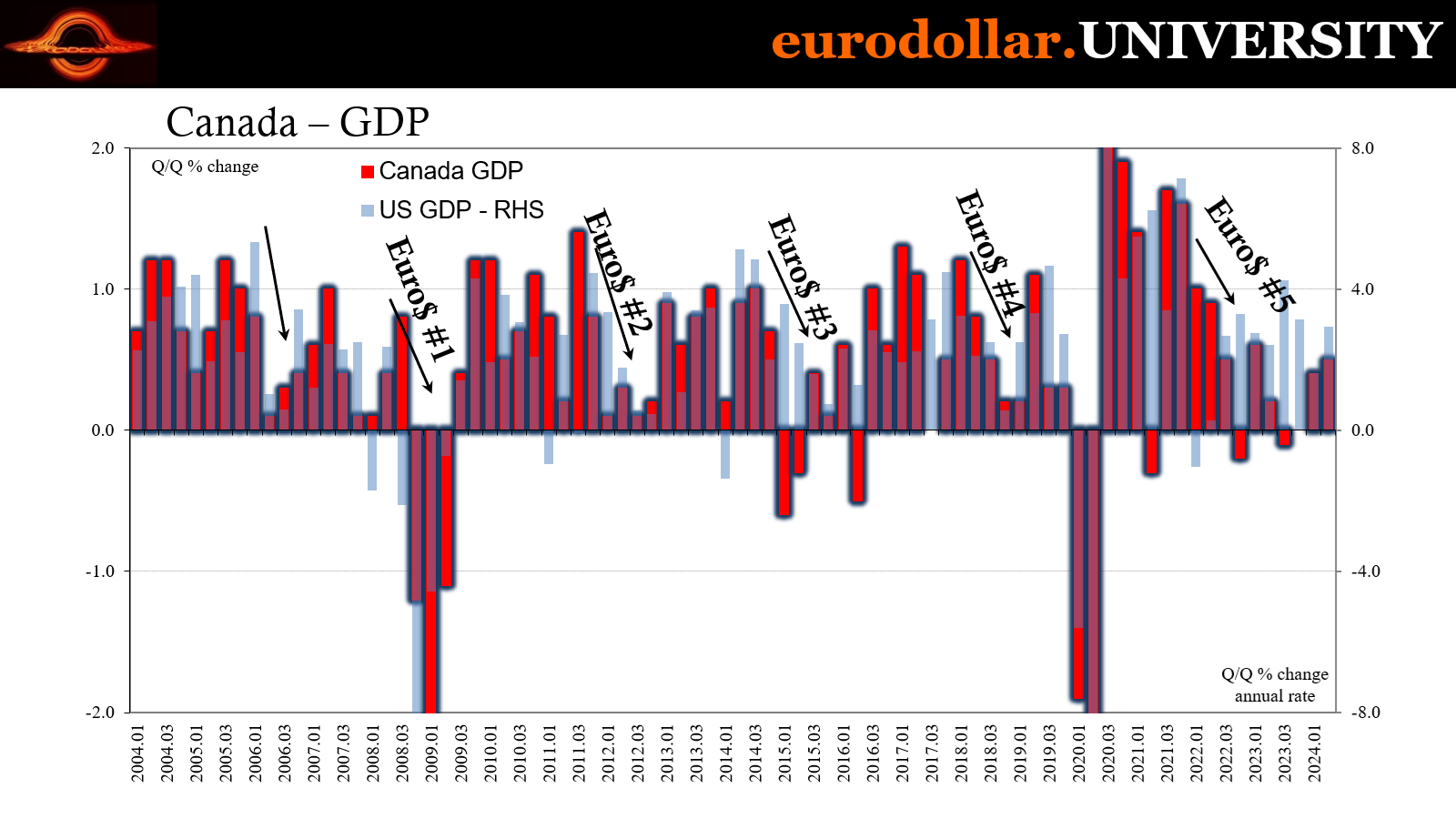

The US-Canada synchronization obliterates the entire line of thinking and instead puts the eurodollar at the forefront.

It would be easy and a mistake to dismiss it as the product of proximity. There are a number of critical differences despite the pair sharing a long border and quite a bite of long-ago history. On paper, the differences are more profound than the lack of geographical separation. Yet, starting with consumer prices, it’s clear there are major forces acting in concert on both at the same times.

They aren’t exhaustive which is why there remains some distinctions, though those are clearly minor leaving the vastly more important trends as in common. Though the eye test is more than enough evidence, I’ll provide some math to back that up. A simple regression analysis shows a really high degree of correlation in consumer prices (and it doesn’t matter which version, the US CPI or PCE Deflator end up with nearly identical results if the latter at a lower indicated rate overall; I’ve previously shown similar correlations among European HICPs or others).

Confronting high prices during the supply shock, the Bank of Canada could have done nothing and the chances of disinflation were high anyway so long as the US experienced it – which, of course, it did. Then the question becomes, was this supranational disinflation due to the Fed’s rate hikes? Or did Canada’s hikes lead to US disinflation?

You really start to appreciate how the central bank and its interest rate policies are starting to be properly seen as arbitrary and irrelevant. If there are global forces acting on both countries simultaneously, not only does that explain why both “central bank’s” policies ended up just as synchronized as consumer prices, more importantly it exposes the corruption at the heart of Economics.

Should the discipline finally admit that there aren’t really national economies, then the question about who should step in when there’s trouble doesn’t have an easy or really any answer. Instead, what immediately springs to mind is how central banks are entirely superfluous.

You can also see in the instances where the Bank of Canada and the Federal Reserve’s interest rate policies diverged, it didn’t matter, either. While both were more often than not in lockstep, during the early to middle 2010s the two were moving moderately in opposite directions; Canada raised rates in 2010 and kept them above the Fed until suffering a recession during Euro #3 when it began to lower them just before the Fed started hiking.

Neither mattered, consumer prices and even the outlines of GDP in both places were more than similar enough regardless of what each institution was doing – Canada fell into recession while the USU came close to a full one. Consumer prices slowed materially in both. The larger implication reverses what we are supposed to assume is cause versus effect: we’re led to believe that central bank policies lead to changes in consumer prices and economy when the data shows that these global price and economic pressures are what end up synchronizing central bank policies!

Policies are, as I always say, reactions to conditions and those conditions are common regardless of anyone’s place in the world. Paul Krugman would belatedly come to this realization in 2016, though to my knowledge he’s been unable to make any use of it other than to finally help explain Japan’s repeated failures.

He nor any mainstream Economist can apply the implications to their theories for the simple reason those theories comprehensively break down in the face of them (rendering econometrics similarly useless). They choose instead to continue pretending central bank interest rate policies are crucial and powerful levers for national economies that don’t really exist, at least not at the level they are currently assumed.

Moving beyond the central bank debate, the more important and relevant matter is what the degree of synchronization between these “economies” might indicate for everyone including central bankers who will inevitably follow it. Canadian consumer prices were just estimated to have fallen sharply; that is, rates of price changes, not prices themselves, have slowed quite a lot in recent months, something else I pointed out for various places around the world.

As of the latest update, Canada’s CPI is now at a 1.6% rate.

It’s another instance for what central bankers will be classifying as “undershooting”, weakening conditions driving consumer price changes into the “bad disinflation” category (as discussed here, there is an enormous, material difference between the kind of disinflation experienced during the Great “Moderation” and what came up during the 2010s Silent Depression).

It has gotten to be enough to concern Economists up north into arguing for the Bank of Canada to accelerate its rate cutting, including doing a fifty-basis point reduction next week.

“With back-to-back lower inflation reports and third-quarter gross domestic product poised to come in well below the Bank of Canada’s forecast, BMO is changing our call for next week’s meeting,” Benjamin Reitzes, rates and macro strategist, said by email.

“Given the weakness in the economy, it’s clear that our 50 basis-point rate cut call will become the consensus,” Royce Mendes, managing director and head of macro strategy at Desjardins Securities, said in a report to investors. “The Bank of Canada needs to do something to revive the economy and stop inflation from falling too far.”

Again, the attention devoted to, and focus on, the Bank of Canada is entirely misplaced. Synchronized price behavior already shows it doesn’t matter what the BoC does, prices are going to follow the system regardless of interest rates. The real matter, then, is whether weak Canadian prices are really an outlier, one of the few times when idiosyncrasies become relevant, or if dramatically slower prices are just more evidence for where the entire world economy/system is heading.

This would be exactly where the swap market has them, Canada and even the Bank of Canada contributing more evidence the system, the whole thing, is indeed moving to where rates go down…and then stay there. Over the last year, we’ve made the decisive move toward the first part, rates going down and by more than a little which in a synchronized global context would necessarily mean synchronizing central bank actions (if only because of the pretense each of them continue to operate under).

Nearly the entire world (Japan being a notable if likely temporary exception) went from higher for longer to accelerating rate cuts in a matter of months.

With more record low spreads for interest rate swaps – US$s, to be precise – Canada’s weakness really is everyone’s. Think about the harmonization with something like India’s rupee that I discussed a few days ago.

As that weakness continues to spread around the rest of the world, CPIs and such will move in that same way causing central banks to react, completing the process of synchronizing interest rate policies because of the global economy.

That still leaves us with the more important problem of what happens that after pushing interest rates down globally it keeps them there. This isn’t something that can be specific to the US, Canada, or some place like China and we aren’t left with many suspects apart from the supply shock, the one factor everyone had enough in common.

The Bank of Canada will predictably respond to changes in global consumer price pressures and the economy. Not Canadian prices and economy. This process explains their policy changes and why those are simply more evidence for what low rates fundamentally mean.