AGGREGATE MALINVESTMENT

EDU DDA July 19, 2024

Summary: Given the mainstream description of economic circumstances especially in the United State the past few years, the idea of the entire financial world hedging to be prepared for more depression economics seems beyond far-fetched. It at first appears downright preposterous. Yet, the full weight of evidence is on the markets’ side. All that’s really left is to rewrite the narrative which actually fits the facts.

Because we’ve been inundated with ideas of red hot and inflationary economies, the notion of a low-interest rate long-run future at first seems plainly absurd. The economy, we’re told, didn’t just recover from the pandemic lockdowns it over-recovered, overheating to the point we required Jay Powell’s assistance with epic rate hikes to slow everything back down.

What the markets are pricing more and more strenuously, therefore, appears to be wholly inconsistent with fundamentals. But those are only the fundamentals as claimed by a certain set of people with a very distorted view of these distortions. And that’s just what they are and have been, too, and it is exactly those what markets like swaps are hedging against.

To understand the disconnect, therefore to connect a low-interest rate, depression economics (small “e”) future with all the actual evidence we have today only requires a somewhat brief (for me) orientation.

The theory behind much of what’s called Keynesianism, or neo-Keynesianism, is simple enough. Think of what John Maynard had proposed of an economy confronting a recession or a worse depression. He reasoned it would be far better if the government, as the “only game in town”, did something with the multitudes of suddenly unemployed workers rather than let them sit idly by doing nothing for themselves or anyone else.

Benefits would seemingly accrue to both sides: the worker gets a paycheck he or she wouldn’t normally have had while the economy as a whole gains a source of income therefore spending it otherwise would not have. Keynes and his legions of subsequent followers argued the trade-offs were entirely net positive.

They call this is positive multiplier because for every dollar paid to a formerly unemployed worker it comes back through the economy many times over. Even if it gets saved at each and every step along the way, that’s still more dollars or in this case additional cents flowing through the system which otherwise would not. More comes out than what went in.

As a result, fewer additional workers are laid off because there’s more spending which means spending doesn’t ultimately decline to as a low a bottom whereas general unemployment tops out far less, too.

Filling in the troughs.

Keynes himself oftentimes brought up pyramid-building though it was just as often a way to make a slightly different point than most of his critics cheaply claim. He did not say that societies should aim to build economically-useless monuments in the desert or anywhere else; the point he was making was that when faced with dire circumstances of something like depression no one should immediately dismiss such utterly absurd fantasy because under those circumstances even the dumbest ideas, Keynes claimed, are better than nothing.

From his General Theory [1936]:

When involuntary unemployment exists, the marginal disutility of labour is necessarily less than the utility of the marginal product. Indeed it may be much less. For a man who has been long unemployed some measure of labour, instead of involving disutility, may have a positive utility. If this is accepted, the above reasoning shows how ‘wasteful’ loan expenditure may nevertheless enrich the community on balance. Pyramid-building, earthquakes, even wars may serve to increase wealth, if the education of our statesmen on the principles of the classical economics stands in the way of anything better.

The first lesson Keynes preached for general economics is, don’t let the system ever get that far in the first place - a point I think we can all agree with. But should it, then do everything possible to lessen the negative effects, including “wasteful loan expenditure” from the private sector or, if necessary, equally useless white elephant projects financed by the only borrower who may easily borrow at those times: government.

Keynes’ general point was demand drives the economy, meaning aggregate demand. He was far less enamored with what the Austrians call malinvestment. This other concept is when bad projects financed by bad money lead to dead-ends in the economy which if they aren’t swiftly and mercilessly dealt with produce what might look like an ongoing negative multiplier because bad ideas constantly suck in more good money leaving less for good ideas. Malinvestment is a drag and a persistent one on future potential.

Building pyramids would qualify as it would require taking productive assets and using them to construct unproductive outcomes. Keynes agreed arguing, again, the difference being the circumstances.

Considering those, should we also consider the possible negative consequences of unproductive actions taking in the depths of recession or depression? Put another way, might “aggregate demand” created as Keynes advised end up becoming enough malinvestment to the point any short run positive the “stimulus” might have created is overturned through time by eventual harm it will do?

I don’t mean, necessarily, strictly shovel-ready projects as they were once called just a little while ago. The ARRA of 2009 and 2010 became so widely-appreciated for its absurdness that for a time it turned the word “stimulus” itself into a running joke. Forget positive forward multiplier, there was the real problem of not being able to first identify any immediate impact.

Obama was far outdone by the pandemic age, both Trump and Biden. Furthermore, the “aggregate demand” tactics employed by each administration heavily rested upon not pyramids instead direct transfers. People weren’t paid to work for the government, they were instead paid to not work at all.

I have a hunch Keynes would have been horrified, not that it matters now.

But if there were no pyramids then could there have been any malinvestment? Does handing money to former workers somehow avoid the trap of wasting public funds making useless monuments that will be a drag on the public economy for some time forward?

What the Austrians do understand that Keynesians appear unable is that any distortion due to non-economic factors (like religious idolatry, earthquakes, even wars or irrational lockdowns) will create massive and most likely harmful ripples throughout a system. Taking productive workers and making them create unproductive things is only one form.

Consider what happened in 2020 and 2021, particularly the latter following the third “helicopter” financed by what came to be called the American Rescue Plan. Americans immediately spent a ton of their windfall and did so at a time when the global supply chain from manufacturing to shipping was still waylaid by government restrictions. Prices naturally soared as economic (small “e”) law dictates.

That wasn’t inflation – it was malinvestment. There is a case to be argued it was necessary to prevent worse from happening to a reeling global economy, and though I would take the other side that’s not our focus here today. What’s done is done.

If aggregate demand theory works, then when the workers who get siphoned off to do unproductive things get sent back into the workforce during recovery. They somewhat easily transition from the government to the private sector, though it would always be messy and fraught with friction; in the end, it works out to a net positive.

The same was supposed to happen in 2021. Uncle Sam (and other governments like those in Europe which paid for furloughs) made his payments with the idea they would be spent – they were – and that would lead to the virtuous economic cycle described above. That did not happen.

It could not have. Think about where all that money ended up. While it did get transferred from the government (financed by the banking system, which we have evidence for) via businesses and mostly consumers, a huge portion went overseas either to pay for oil or for goods made elsewhere and then shipped by foreigners back here.

What jobs might have been created, or, more realistically, brought back from furlough when the whole country splurged on Amazon.com? For this large proportion of “aggregate demand” quite a few should have been in Asia though even then it was less than you’ve been led to believe.

It is something which shows up all over the statistics, too, this price illusion. Whether it is Japanese trade or US retail sales, the difference between nominal and real series is unreal yet a very real threat to the global economy entering today and moving forward.

Think about this part of it from the perspective of Japan Inc. Americans in 2021 blow up Amazon with orders for goods a lot of which are made or assembled in Japan (from China). But “blow up” didn’t mean necessarily the number of goods; the price surged because Japanese firms couldn’t find and obtain enough components to make enough goods or what they did manufacture wasn’t easily transported. Since US consumers (and others around the world) had “free money” they didn’t care the price soared.

Everyone simply paid it. We paid more to get less.

Japanese companies got a windfall but also had no reason whatsoever to do anything productive with it. Why would they? The amount of goods which needed to be made or exported didn’t really go up all that much, or if it did it didn’t stay up for very long. Japan Inc. didn’t need to hire a ton more workers in Japan or anywhere else because there was nothing more for those workers to have done. This distortion didn’t close the loop as a recovery would precisely because it was inorganic and forced; malinvestment.

These distortions weren’t entirely foreign, either. What did stay domestic meant a large wage increase to the already-working rather than make available jobs for those who had been let go during the lockdowns and their aftermath. Pay for the employed surged while for the unemployed the government stipends dried up and left them worse off with no available employment and now further behind due to price changes.

Too many were stuck in the latter category and, once again, we have tons of evidence for this.

Millions upon millions fewer are today working than would have been had there been no lockdown interruption. According to the Household Survey from the BLS, it’s on the order of eight or nine million. Even the questionable Establishment Survey shows a deficit of four million. And these are on top of the tens of millions of jobs we’re still short of the pre-2008 potential.

In short, a whole ton of “aggregate demand” got channeled in the most unproductive ways, maybe the most unproductive ways in many ways possibly worse than had Uncle Sam made the idle unemployed during the lockdowns report to local agencies to build pyramids in every county in America. We paid shipping firms and oil producers in Saudi Arabia for what? It’s not as if Maersk and Aramco used the money to hire millions of American workers which is what an aggregate demand program demands from itself.

That’s ultimately what “unproductive” means. Hundreds of billions were funneled to businesses and countries that just sat on the proceeds, they dead-ended as profits to companies which benefited the most from the supply shock. Then where did those profits from there? They were supposed to get cycled back into new jobs either hiring or building new productive facilities. The evidence conclusively shows neither took place.

Those windfall profits were reinvested not in productive ways to build more ships, pipelines, oil pumps, or even factories somewhere. They largely got saved which in this environment meant and still means Treasury bonds or other kinds of safe and liquid assets (including Blue Chip-type stocks, equally unproductive).

Think about it this way from beginning to end: the government handed out borrowed cash which got spent and eventually so much of that cash ending up as one-time profits reinvested back with the government. Not new workers. Not new investments. Safe and liquid assets. If that doesn’t sum up “unproductive”, nothing ever could.

The world didn’t get more out of it than what was put in, instead we just paid more in nominal terms to get less. This imbalance is what drives the downside of the supply shock because that cannot possibly go on for the long run.

What that means is that the nominal side of the global economy has to adjust down to the real side, not the other way around. Nominal incomes will slow to better match real purchasing power which, given the massive jobs deficit, is a particularly scary thought. Nominal trade will have to come down to better align with the actual amount of goods produced and then exported. Retail sales will have to slow and even contract in order to match the real flow of actual goods.

This, by the way, is exactly what OPEC and Saudi Arabia have been doing in their own sector. It is a form of deflation caused again by the fundamental distortion of the supply shock, only here the cartel is attempting to hold on to those prior price gains by sacrificing output. That means fewer profits (and potentially workers) giving back more and more of that previous 2021 windfall!

Eventually, they’ll be cutting back on workers, too (this is already happening as the government in Riyadh is tightening its spending on other projects).

Malinvestment is a drag on potential so long as it keeps being maintained. At some point, there has to be a lot more like OPEC across all industries (including services) and national boundaries which far better aligns with that reduced potential. Economics (small “e”) abhors artificial distortion, which feels like instability so long as it remains because it is unstable.

The way in which it eventually finds a stable state is…unemployment.

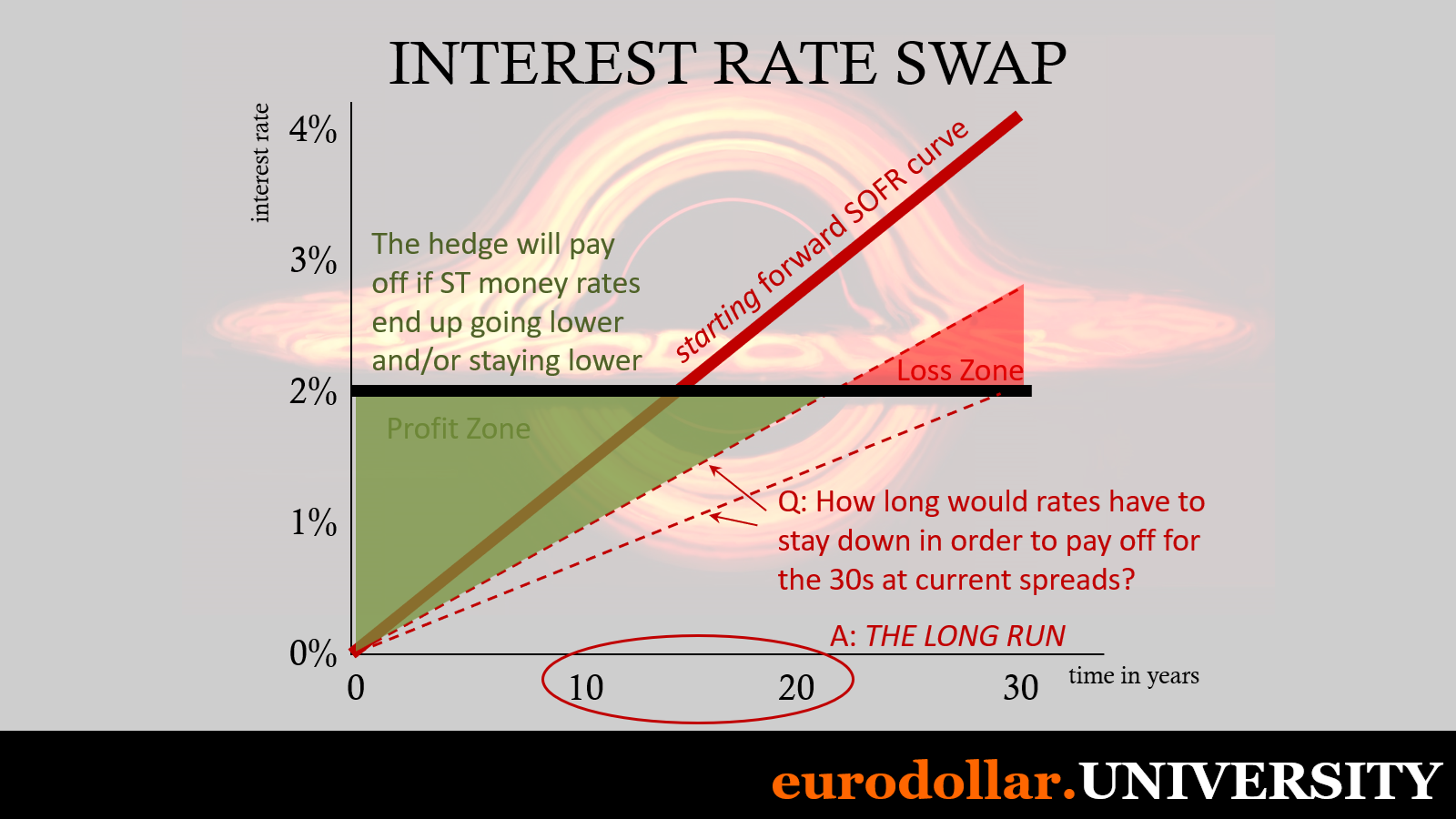

Given the scale of these disparities and how widespread they are, is the fundamental idea priced into the swap and bond markets right now really all that far-fetched? If those are indicating more strongly a long run interest rate environment which looks too much like the 2010s, the unproductive malinvestment of the early 2020s is the key reason why.

We also need to keep in mind that potential was already greatly impaired by the last time, meaning 2008. So we have a double-dose of negatives one piled on after the other. In macroeconomic terms, how could it not be like the 2010s just worse?

What that ultimately means isn’t at all clear. How many jobs need to be “given back” and how much nominal income needs to be reduced, there’s not any real way to make useful judgements. Complicated and messy doesn’t even begin to describe this process.

The most we have are these very broad outlines: on the one hand, the swap market and the eurodollar system consistently pricing the downside to the supply shock leading to a long run with low interest rates, meaning depression economics (small “e”); on the other, datapoint after datapoint showing the scale of the price illusion which was a measure of malinvestment even if it doesn’t necessarily look like the usual aggregate demand wastefulness.

You can at least appreciate, I hope, why there would be so much and growing demand for hedging for those kinds of scenarios. Those scenarios are at the end of the downside to the supply shock.

“We” paid so many millions not to work so that they could pay trillions for companies not to make more things that ended up with those trillions back where they started. It’s not economics so much as plain common sense. There was always going to be a heavy price to pay for those unproductive distortions. The only question was when. Well, that and how much.