THE REAL SIDE OF GDP

EDU DDA Aug. 29, 2024

Summary: Summary: The US Treasury market continues its aggressive bull steepening, with more parts of the yield curve un-inverting including the 2-year/10-year spread for the first time. At the same time, the US govt reported an even better second quarter GDP estimate. How can we reconcile these two very different signals? Easy: use GDP's opposite side. Unlike the more famous version, the other one is flashing all the same warning signals as Treasuries, the unemployment rate, even overseas economies.

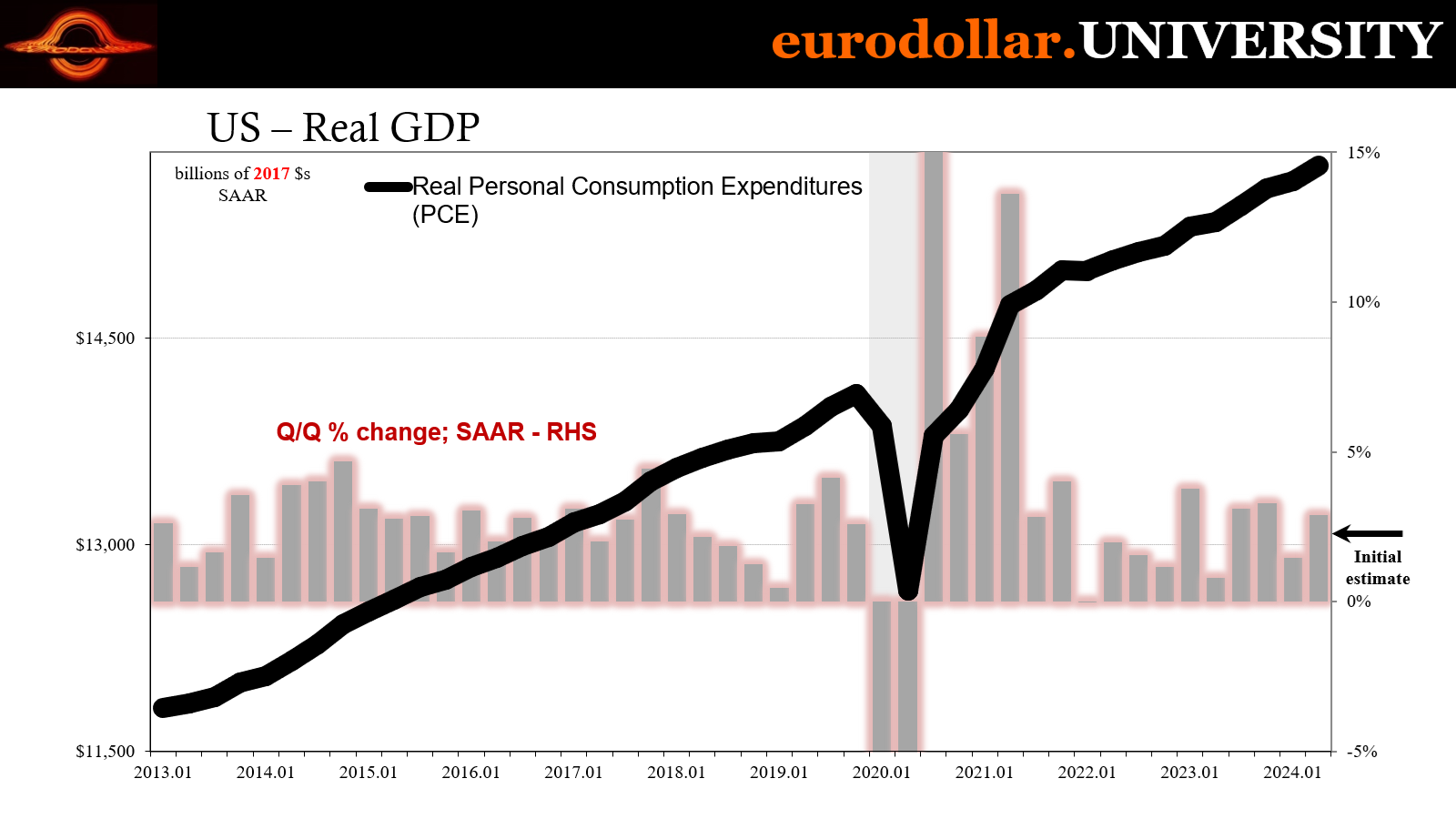

Yesterday, the US Treasury curve’s 2-year/10-year spread un-inverted for the first time this cycle, a significant milestone as the whole curve continues to unwind in decisive fashion. This broadening bull steepening is not a good sign. So it was fitting today the US Bureau of Economic Analysis upgraded Q2 GDP by another tenth, putting it just shy of 3% on the purported strength of more robust consumer spending.

These two measures are in direct conflict with one another. In fact, GDP is in conflict with a bevy of data beginning with…itself.

Unfortunately for us and GDP, its second estimate comes with the initial round of GDI numbers. Unlike their more famous flipside, the GDI data and its wealth of details is very much in line with the yield curve’s behavior over the past several years leading up to now, plus the increasing recession probabilities which go along with the curve’s conclusive swing toward bull steepening.

Taking the latter first, the un-inversion on the curve has been unfolding for several months already. The 5s10s spread started way back in the middle of June under the cover of European election uncertainty. Hindsight now clearly shows it wasn’t voter-driven uncertainty instead sharply higher US recession probabilities plus what those are doing to prospects for the global economy as a whole.

This is why, for example, we see June 13 show up as the first date when the 5s10s reached zero after being inverted. That date is also all over the swap market as well as European bonds (bunds, especially). Since the most visible suspect at the time was the political turmoil enveloping France and what that was doing to the European marketplace (stocks as well as OATs and French bond spreads), it seemed a logical connection at the time so the true significance was obscured at least for a little while.

Over the two and a half months since, particularly when factoring that little liquidation chaos at the start of this month, the trends which amplified back in mid-June must be unrelated to the European political situation which has largely resolved itself. Again, the real culprit over and over appears to be US economic woes.

That 5s10s un-inversion has since steepened as has the 2s30s spread, now reaching +30 bps after initially reversing in mid-July right after the US June CPI report was released. As previously discussed, those CPI estimates (and their July follow-up) weren’t simply disinflationary, they were “too” disinflationary therefore confirming a lot of the negative suspicions priced into these curve and market dynamics.

Now it is the 2s10s which are making the same shift, meaning the un-inversion and bull steepening is and has already broadened out beyond any threshold of mere random fluctuation.

So, how does that happen with now-three percent second quarter GDP?

There are two explanations which are not necessarily mutually exclusive, though the second one is, in my view, the most likely. First, Q2 is a long time ago meaning whatever the BEA might have found during that time is already stale old news. Events have superseded whatever strength the government had picked up nearly three months ago.

It’s entirely plausible due to the fact GDP itself varies greatly before and even during outright recessions. In the early stage of the Great not-Recession, Q2 2008 GDP rebounded strongly from Q1 2008’s initial contraction (since revised much deeper) rising 2.37% q/q (annual rate) and for a time allaying many fears (sounds familiar) the US would suffer a contraction due to “subprime mortgages.”

Just before the dot-com recession in 2001, Q3 2000 GDP was barely positive (+0.41% q/q) then bounced back by 2.38% q/q in Q4 only to fall 1.31% in Q1 2001 before jumping +2.49% in Q2 while the dot-com recession was already underway. Wild quarterly variation is nothing new to 21st century cycles.

Even so, I don’t necessarily think that explains the current behavior of GDP versus so much else lined up against it. Instead, the answer – or more of it - comes from GDI.

For those who many not have encountered GDI before, which isn’t unusual, this measures the economy from the other side of GDP. Whereas the latter calculates how much money has been spent on goods, services, or productive investments, every dollar spent must also be a dollar of income for someone on the other side, the GDI income side.

The two, by intention, should match and for most of their history they actually do, at least close enough to be within reasonable tolerances and margins for error. However, the two do depart and most visibly surrounding economic inflection points, those times when recession is developing. And during those, it is GDI which provides a more accurate measure of where the situation stands.

Going back to those prior cycle switches, GDI picked up on the Great not-Recession as early as Q3 2007. It had experienced a sharp loss in that quarter – the very same when the full crisis of August 9 happened – then only a tiny retracement in Q4 before five straight quarters of increasing declines throughout 2008 into 2009. GDP, as noted above, was back and forth in the first half of 2008 appearing to show economic strength and resilience in the face of fierce financial headwinds that really were undermining everything.

(NOTE: GDP did a better job in the 2001 cycle, though it was GDI proving again more accurate before and during the initial stages of the 1990-91 recession and the others before then).

It is a perfect encapsulation of this difference; an economy that is weaker than otherwise believed would necessarily and logically be more susceptible to plunging into recession and therefore be more of a surprise and shock to those relying more or solely on GDP.

In addition to this historical performance, GDI more recently is also far more consistent with the marketplace signals, not to mention globally synchronized. We see a more defined and more importantly sustained downtrend in GDI going back to early 2022 when curves first inverted; the transition from supply shock upside to downside left more of a negative impression on GDI than GDP.

Exactly what’s been in European, German, etc., GDP and similar. Those economies fell straight away into shallow yet prolonged and no less painful (especially through more time spent this way) contraction right as European curves inverted and has been trending sideways ever since (which is contraction in a non-linear world). That is just what US GDI has done, contrasting more sharply with US GDP by being closer to overseas versions.

While even GDP itself has suggested a modest downturn, GDI is more consistently recession-like which also matches popular perception wrongly written off as nothing more than a “vibecession.” As I wrote not long ago in the DDA, the idea of a “vibecession” was offered in the middle of 2008, too, supported by what GDP indicated instead of more seriously factoring where GDI was and was heading.

Regular people better understand the real state of the employment market and GDI better picks up what those people are understanding.

The discrepancy between GDP and GDI has been discussed in various cycle inflections through history, including 2007. Then, it was dismissed as inaccurate for given reasons that fell short of honest analysis; it didn’t fit the overall narrative, impression, nor agenda. The debate was revived earlier in our current cycle right as it was turning.

The minutes for the FOMC’s June 2023 meeting record:

In their discussion of economic activity, several participants pointed out that recent GDP readings had been stronger than expected earlier in the year, while gross domestic income (GDI) readings had been weak. Of those who noted the discrepancy between GDP and GDI, most suggested that economic momentum may not be as strong as indicated by the GDP readings. In discussing that possibility, a couple of these participants also cited the recent subdued growth in aggregate hours worked.

Given the way the labor market, in particular, has turned out since then, more attention really should have been paid to GDI. To begin with, unemployment started to rise and then grew more serious during the third and fourth quarters of 2023 when GDP in both was surprisingly and suspiciously strong (admittedly, GDI was somewhat better during last year’s second half, too, though in the wider context it was more of a fluctuation than something resembling resilient strength).

On top of consistency, GDI also contains data related to labor market indications that offers better color behind changes to employment conditions. The components which make up GDI start with compensation of employees, subsidies paid by the government, an estimate for capex (fixed capital) and then include a measure of private business profitability, something called the Net Operating Surplus (NOS).

It is just as the name proposes, a proxy for profits excluding non-economic additionals such as those government subsidies.

NOS in nominal terms has been sideways since the middle of 2022, meaning sizable contraction even before price/cost increases. With no additional profits from the “strong” economy the past few years, not only does that bely the very notion of strong and resilient you can already recognize the very reason why the jobs market would have softened so much.

We can compare the NOS to how much GDI (meaning income) is devoted to compensation of employees rather than accruing to employers’ bottom lines. What we find is how much of it has gone increasingly in the formers’ favor with no clear economic gain for having done so – you could argue it was the necessary cost of the “labor shortage” but even if so that cost will have to be paid in the future and if it isn’t recouped by legit economic expansion then real trouble lurks.

We can derive a proxy for that trouble by comparing the share of GDI going to NOS (profits) versus employee compensation plus capex investment and then measuring it by the year-over-year change. When the yearly change turns negative, this means profitability as a share of overall economic income is shrinking compared to labor costs and productive investment, so naturally those are times when we would expect businesses to pare back on either of those if not both.

If firms are not generating as much profit from the economy and instead spending more for labor and investment, they will seek to restore profitability by trimming costs in the absence of a credible path to reclaim those profits in a truly strengthening future economy. The latter situation is recovery and we see that in strong positive changes in this measure; conversely, recession is the former and it is preceded by those times when this number is negative as it has been consistently since the start of 2023.

(NOTE: this measure derived from strictly GDI components is backed up by another one with a longer history using annual data, so not as timely, which alternatively focuses on non-financial profits in NOS; the two come to similar conclusions about the ratio of profits to payments)

Sure enough, labor data independent of GDP increasingly validates that idea. Businesses are seeing less upside and whether freed from the “labor shortage” or not we have numerous corroborating accounts (including payrolls, at least when revised by QCEW) showing a slowdown and worse in labor most likely a result of what this GDI ratio intends to quantify.

GDI adds up to vastly more of what we see across the markets and economy. There are historical reasons to prefer GDI, the consistency of globally synchronized, not to mention it more closely matches the public’s general perception of the everything since the start of 2023. The GDI trend also far better aligns with the inflection in the labor market last fall and the turn toward full recession this year showing up from multiple angles.

Quite simply, if the US was in substantially more trouble entering 2024 than otherwise believed, what seems to be unfolding right now wouldn’t be much of a leap, just the next logical step in a progression that’s been unfolding for quite some time.