EUROPE ABOUT TO CUT RATES FASTER AND FARTHER

EDU DDA Sep. 24, 2024

Summary: The Chinese did, indeed, cut rates - a lot of them and by a lot. Aside from that panicky confirmation, we turn our attention to Europe where various curves continue taking substantial twists. Interpreting them means considering possibilities only now being admitted by either central bankers or mainstream sources. Not just some macro, layoffs risk. Looking behind the last European rate cut also introduces something else.

The PBOC did, as expected, announce an entire suite of rate cuts at its press conference earlier today (Beijing time). Rather than just one or two, authorities decided to take down pretty much everything and by more than the usual small increments. While there were some details about when and exactly how much, in this case it doesn’t make any difference.

Chinese officials just confirmed they see a growing downside, therefore opted for their version of “shock and awe.” The problem is it is only impressive to other Economists, maybe a few central banker types and speculators in certain risky markets these same authorities always blame when they speculate the “wrong” way. Copper and stocks in China are up, but they won’t be for very long.

Rate cuts don’t work. These same rescue measures have already been tried. After the euphoria calms down over the weeks maybe only days ahead, reality will rudely intrude with nothing substantial having been changed in between. After all, market interest rates are already significantly lower with nothing stimulated for them.

Lower rates are always bad news.

For the full rundown of what went down, either check out today’s Daily Briefing or I went over them – and why you shouldn’t expect much from any of it – over at YouTube. It was Oprah at the PBOC.

The actual subject of this Deep Dive is Europe with forward rates and curves moving sharply, the latter especially at the front leading to major un-inversion and bull steepening. While the American economy has garnered most of the attention and focus since the “recession scare” broke out into the public realm late in July, emphasized even more by the Federal Reserve’s outsized rate cut last week, and China is angling to gain it back with its panicky quasi-bazooka attempt, there is a lot about Europe which demands scrutiny.

From the macro side, it’s basic and straight forward. All the evidence continues to show, first, the seasonal pattern. That is, every year post-supply shock the economy appears to be picking up around spring, sparking talk even expectations for recovery, only to see them dashed by summer. This year was, sadly, no different.

Everything from hard data like IP or GDP to especially the sentiment surveys and, in particular any of them having to do with Germany, has strongly pointed to a second half downturn. What makes it worse this year as opposed to last year is the growing danger to the employment part of the economy, the potential to surpass the unknowable threshold between labor hoarding and rapid de-hoarding.

That’s the minimum indicated by how markets are evolving, the radical twisting and bottoming on these curves like EurIBOR futures or just plain cash market bonds (bunds).

The thing is, we keep coming back to the already-done rate cuts specifically from the ECB and not just in European markets as a critical trigger. That June policy pivot looms large over an unusual number of charts around the world.

At first, those mid-June shifts seemed to be tied to the European elections. It was logical enough, particularly with French bond spreads surging to troubling levels and triggering a backlash across bonds and even US$ collateral (4-week T-bill rates show this, for one example). However, lost amidst the political drama, the ECB had, right before then, voted for a somewhat unexpected rate cut.

“Unexpected” in the sense that the cut was a clear violation of the prior pledge to keep hammering away at “inflation” with higher-for-longer and only moving from it once Europe’s consumer price measures were below the target. Back in June, the HICP as well as CPI were still substantially above and, worse, showing signs of “stickiness” (according to Economists’ interpretation of the numbers).

Officials blatantly ignored it. What was therefore a more radical departure for rate policy than anyone outside the markets caught on, lost amidst the French partisanship, signaled a very dramatic change in the perceptions of macro and maybe more risk (I’ll get to the “maybe more” a little further on).

To show you what I mean, take the swing in EurIBOR futures. Before then, they had been pricing a modest inversion therefore a decent though hardly overwhelming chance for an accelerating series of rate cuts out of the ECB. Some of that was due to the “stickiness” debate and how it appeared, for a time, to hold sway over enough of the voting members.

In other words, the market judged it would take a lot to refocus priorities; or, exactly what did happen from the middle of June.

The ECB voted for the rate cut and even though they paused in July, the market sensed it would be more than just a single twenty-five reduction every other meeting as apparently has been the plan since then. The Euribor futures curve has plunged steadily from the middle of June, therefore it never was the election stuff.

While that might at first seem nothing more than the market getting the OK from Christine Lagarde to gently revert policy levers back to the pre-hike levels, the expected long run rates as estimated by central bank models, the real matter here comes down to speed plus intensity. Back at the time of that first cut, policymakers in Europe had not intended to do much more than what they’ve done so far – a leisurely unwinding of “restrictive” rates covering a few years after which the nominal ST rate would be higher than before.

Like SOFR futures and US$ curves, however, the European version has more and more aggressively bid beyond that. Not only are these markets pricing in more rate cuts from the ECB, they’re also pricing those to come faster and heavier thereby ending up much lower and closer (if not surpassing) to 2010s.

More recently, several ECB officials have, not surprisingly, expressed their desire to be more like EurIBOR futures than not. While there are some remaining hawks, perhaps Lagarde being one, though she seems more to straddle in between than make any decisive interpretation, more than a few (such as Portugal’s Mario Centeno) have stated their preference for some urgency.

It isn’t just EurIBOR futures, as other markets are also sensing something negative is up. From earlier today:

Traders are growing increasingly confident the European Central Bank will cut interest rates again next month as evidence mounts the economy is weakening.

Money markets imply a roughly 60% chance of a quarter-point reduction in October, up from around 20% last week. The latest leg of the repricing was driven by US data that showed consumer confidence unexpectedly fell in September.

A large half-point cut from the Fed last week has raised concern over the outlook of the global economy more generally and piled pressure on ECB officials not to fall behind in lowering rates. Governing Council member Madis Muller said on Tuesday he isn’t “totally” ruling out another interest-rate cut next month.

Incoming data, as mentioned, has been more decidedly negative, but there seems to be lot more than just ECB finally coming around to an ongoing recession that’s been ongoing for around two years already. In the near-term, a shallow recession taking on the properties of layoffs would definitely be in the right area.

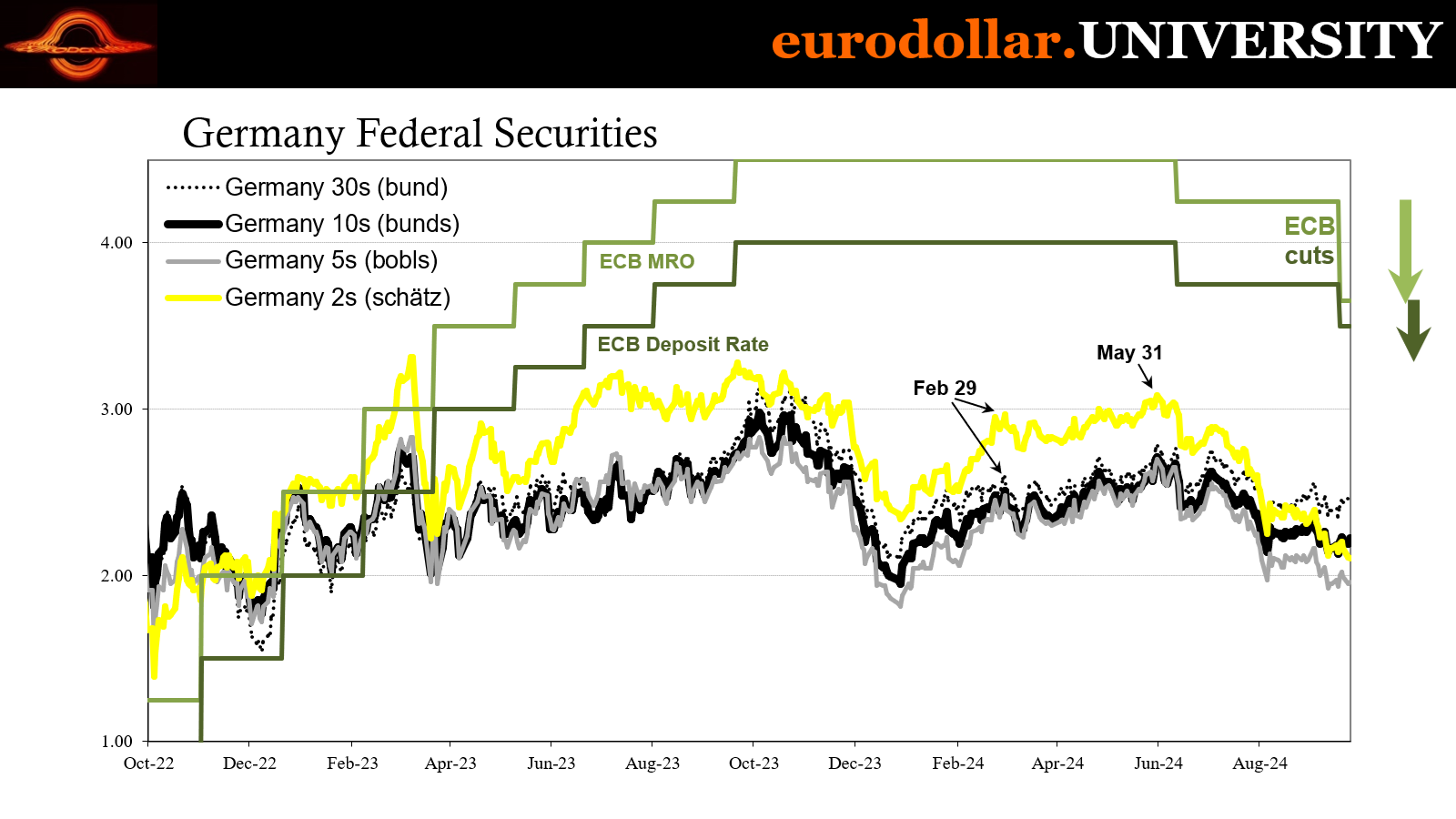

ALONG WITH FORWARD RATE MARKET SHIFTS, BEAR STEEPENING LIKE THIS IN THE BUND MARKET IS NOT A GOOD SIGN.

Turning back to EurIBOR futures, the curve – if taken literally, which you should never do – has ST money rates falling to around 3% by December (give or take a probability spectrum with a pretty wide variation). The current deposit facility rate – where EurIBOR usually goes – is 3.50%. The market isn’t just pricing a decent chance of October plus December, there’s the not-insignificant possibility of a fifty being one of the two (more likely December).

It goes further from there. By the December 2025 contract, ST rates in Europe are pointing to somewhere around 2% with a heavy skew further to the downside. This would be well below the trajectory officials have in mind, one that is very similar to what’s being priced into SOFR futures in US$ terms. Globally synchronized job cutting?

Since so much of this goes back to the ECB rate cut in June, it has to be considered more than simply a policy shift, the pre-programmed pivot. Instead, it was confirmation that officials had realized they were wrong about consumer price dangers. As I keep pointing out, if central bankers can see it then it has to be serious.

To what extent this might extend beyond strictly the macro realm is more debatable, yet one worth considering. There are the usual obscure bogeymen in Europe as the US, the globally synchronized commercial real estate busts. Perhaps related to that, or even for other unknown reasons, is there potential for illiquidity among the European banks?

It was little-noticed at the time a few weeks ago, a quirk to the September rate cut from the ECB saw the MRO and MLF rates lowered by 60 bps, not 25 like the deposit floor. This wasn’t outright panic among Lagarde’s fellows like what we’re getting from China today, rather a pre-planned measure to tinker with the money rate corridor in Europe for some interesting reasoning.

The central bank influences euro-denominated money rates via its three main levers. There is the MLF which acts as something like a ceiling (in theory), with the deposit facility being the intended floor, or, more accurately, soft floor. The MRO, which used to be the main policy target before the era of “abundant reserves”, is put in the middle.

These are not selected randomly, as each of those is meant to perform specific functions all with the purpose of keeping ST money rates right in the area where policymakers want them. Money markets are messier than they are made out to be, and central banks don’t actually control them in the manner or as easily as commonly claimed.

By placing the MRO closer to the deposit rate, narrowing the corridor in the process, officials intend to reduce the potential volatility in euro money markets. With the ECB scaling down its balance sheet via QT thereby, simple arithmetic, cutting down the systemic level of bank reserves, that means money market rates won’t be pressed down to the deposit rate floor.

One consequence of less-than-abundant reserves is more market-like behavior which means variation and potentially a wider degree than policymakers would like to see. By lowering the MRO relative to where money rates are, the ECB has moved down the potential arbitrage point which should, in theory where there is no stigma, mean dealer and other banks might borrow at the MRO rate in order to relend in the market, keeping market money rates altogether lower than they might have been with the MRO relatively higher in the corridor.

The arb trigger is lower raising the chances reserves will flow from the ECB into the market at lower rates thereby limiting any volatility in them and keeping more market-driven ST rates near to where officials want them.

All that sounds relatively benign, hardly anyone even notice the MRO and MLF had been reduced by 60 bps a couple weeks ago.

Where this gets potentially sticky is the reasoning the ECB gave to the European “Parliament”, referencing a short commentary written by authors at think tank Bruegel, meaning they implicitly agree with what was in it:

The effectiveness of this insurance policy remains to be seen: if there was stigma in borrowing from the MRO, because this could indicate inability to borrow from the market, the market rate would not stop at the MRO rate.

In a way it is good that so little is decided and so much is left to the future. Currently, there is not enough information – for instance about liquidity demand from banks or the future distribution of liquidity across the euro area – to delineate more precisely the operational framework that should prevail in the steady state.

While ostensibly focused on liquidity as a function of central bank balance sheet levels, therefore the abundance of reserves, implicit in the nod to “stigma” is the greater concern over bank balance sheet constraints as a whole, the actual and effective systemic liquidity.

What the ECB effectively decided is…that it didn’t have near enough information or experience to do much more than just narrow the corridor as a default blanket insurance. Not knowing what else to do, they just threw this one out there. This should strike people as odd for a number of different ways. In the context of balance sheet normalization at least when combined with the planned gentle removal of “restrictive” rates, there would be little need for such caution.

We are no longer on that plan and what’s more the ECB is beginning to realize this. I’m not saying officials have or had any specific danger in mind as far as liquidity or banking matters, instead like on the economy people may not realize the risks are far higher even so far as policymakers consider them. That’s why they narrowed the corridor because they understand the potential is above trivial – and that’s with the anticipated benign unwinding of the past few years under the cover of a recovering economy.

Sure, the ECB has moved the MRO (and MLF) down out of an abundance of caution, but there is a reason for it and the move itself has signaling implications (“timid”). If the ECB isn’t all that confident in its own effort, then like the rate cutting plan which is increasingly being tossed out the window, what else is there hiding in the shadows?

To be clear, like the ECB I don’t have anything specific to give you as far as a named and detailed threat. Instead, working backward from the market curves and those being perceived and priced in them, they don’t strike me as little more worrisome than prolonging the shallow recession just in Germany. Even some layoffs don’t necessarily get there.

It is the path toward deflationary recession. While it may not be the base case, everything that keeps coming up keeps that road and possibility alive. To have one, though, would, again, be more than just a little more recession, a bit worse on macro plus something monetary. Europe has a lot of the ingredients, we just can’t see them cooking in the kitchen just yet.