‘SCIENCE’ OF RATE CUTS

EDU DDA Sep. 16, 2024

Summary: This week is off to an auspicious start, rate cut hysteria in full bloom. Setting aside the ultimately irrelevant matter of fifty vs. twenty-five, what is a rate cut supposed to be? It sounds like a stupid question - the Fed lowers interest rates. Which one or ones? What, exactly, does that do? How is this supposed to work? No one ever thinks too much on it which is precisely the purpose. Here we'll answer those questions using their own words and studies, starting with Mr. Bernanke.

SAME GUY LESS THAN A DECADE APART WITH THE EXPERIENCE IN BETWEEN REVEALING MORE TRUTH THAN ANY AUTHORITY HAS LET ON.

On Wednesday, the FOMC will vote to reduce its policy benchmarks and beside the fifty vs. twenty-five debate, the more important question is what will happen next. The short answer is…a lot more rate cuts to follow. But why? What is it about them that elicits so much awe but at the same time thorough disappointment. No matter how many times they fail in the past, everyone is right back on the bandwagon for the next ride.

This time is always different when it comes to perceptions of the Fed.

The reason I bring up academic studies and other primary source materials like transcripts or contemporary articles is actually simple. Who am I? Science is supposed to be about examining evidence meaning the facts stand for themselves regardless of who is presenting them.

But that’s not how it really works. It does, certainly, in the hard sciences where a mathematical proof, for instance, discovered and validated yesterday will continue to be valid until it might be overtaken by some other proof. There aren’t the same everlasting parameters in the soft sciences like economics (let alone the bastardized version of it in Economics).

In them, it matters who is doing the presenting rather than what it is being presented. This is the whole reason why Jay Powell is made to look as important and influential as powerful, the ritual of press conferences, speeches, etc., and why the top personnel at the institution must appear to be credible at all times. Whether what they say and more importantly do is useful actually doesn’t matter. They’re playing a part.

Science in Economists is entirely about the scientist, who most times isn’t one.

I hold no fancy degree nor have I ever practiced “formal” Economics. It’s therefore easy for a lot of people to ignore any evidence I might give them because it isn’t coming from the “right” person.

That’s why I use Economists’ own words. You don’t have to take my word for what they are up to, here’s what they all really say.

So, what’s the real purpose behind rate cuts? If you ask a hundred people who would venture a guess, the vast majority will answer with something about borrowing costs. No surprise, that’s what the financial media says not to mention “experts” on Wall Street and even an array of Economists. It sounds like it makes sense.

One category I didn’t include above is the central bankers. These are rarely bankers anyway, most often Economists though of a particular type. There are a few lawyers here or there, like Chair Jerome Powell, yet he’s been so thoroughly steeped in Economics his legal background actually amplifies the effect.

Where that training becomes useful, in a sense, is in knowing what not to say. Officials are very careful to avoid having to admit the uncomfortable truth(s) to what they try to do. When it comes to rate cuts, they can call them “stimulus” yet will never mention exactly how lower interest rates might actually stimulate anything.

Inside the circle of academic Economics, however, it’s a very different story. Read through any number of papers and studies and the truth not only comes out, it is more often than not printed front and center right up at the top in the abstract. They all know not a single member of the public will read them anyway, basically an internal slack channel before one was ever invented.

On the subject of interest rate cuts and how they are theorized to work, we’ll just use the summation written by Mr. Ben Bernanke (along with Ken Kuttner). Though this one is a little dated, that’s actually a good thing for this context. It’s a pre-crisis, pre-QE paper examining the relationship between rate cuts and stock prices (I’ll get to that in a minute).

Starting with the case of interest rates themselves, I’ll draw from another contemporary work to Mr. Bernanke’s this one prepared by the Federal Reserve’s New York branch discussing interest rate policy. Contrary to popular belief, the Fed does not set nor control interest rates, including money market rates up at the very front end.

This is yet another fact which is never discussed in front of the public though is more often than you might think a matter for discourse among the small section of the discipline interested in technicalities. A fed funds target, as back when these were written, or even nowadays with a quasi-corridor often described as a double-floor system (these terms are not important for today’s examination, except to note one more way in which the world just doesn’t work the way “they” always say), is just a place to start for officials hoping a longer sequence of events might eventually somehow work in their favor (with “long and variable lags”).

What’s supposed to happen is that the FOMC votes to reduce rates and that makes borrowing cheaper, first for banks who will then seek to extend more credit given presumed more profitable borrowing/lending spreads. Borrowers are also thought to react since the cost of acquiring funds has been artificially reduced for non-economic reasons, the whole ceteris paribus thing.

The Fed, though, does not control borrowing rates or directly manipulate those factors.

It is natural to question why central banks have abandoned their once-secretive behavior in favor of public disclosures of policy moves. Likely reasons include the desire for better and more precise control of the overnight rate, and, more important, enhanced communication of future policy moves—in essence, the Holy Grail of controlling long rates by also manipulating expectations.

Even the short-term rate set “require” communication from policymakers.

That’s all interest rate policy actually is. There’s no money in it, therefore it cannot be accurately described as monetary policy. Yet, it is. Powell or any Fed official will never say so in public, the entire point of using that term is to link the psychological manipulation to the mythical printing press, an instrument the Federal Reserve does not actually possess.

To be clear: the Fed does use an actual printing press to literally print Federal Reserve notes. What I mean is de facto money printing is done entirely by the commercial banking system and not exclusively in the United States. In other words, since the real economy rarely uses those notes, the direct impact of printing them or threatening to print them is non-existent.

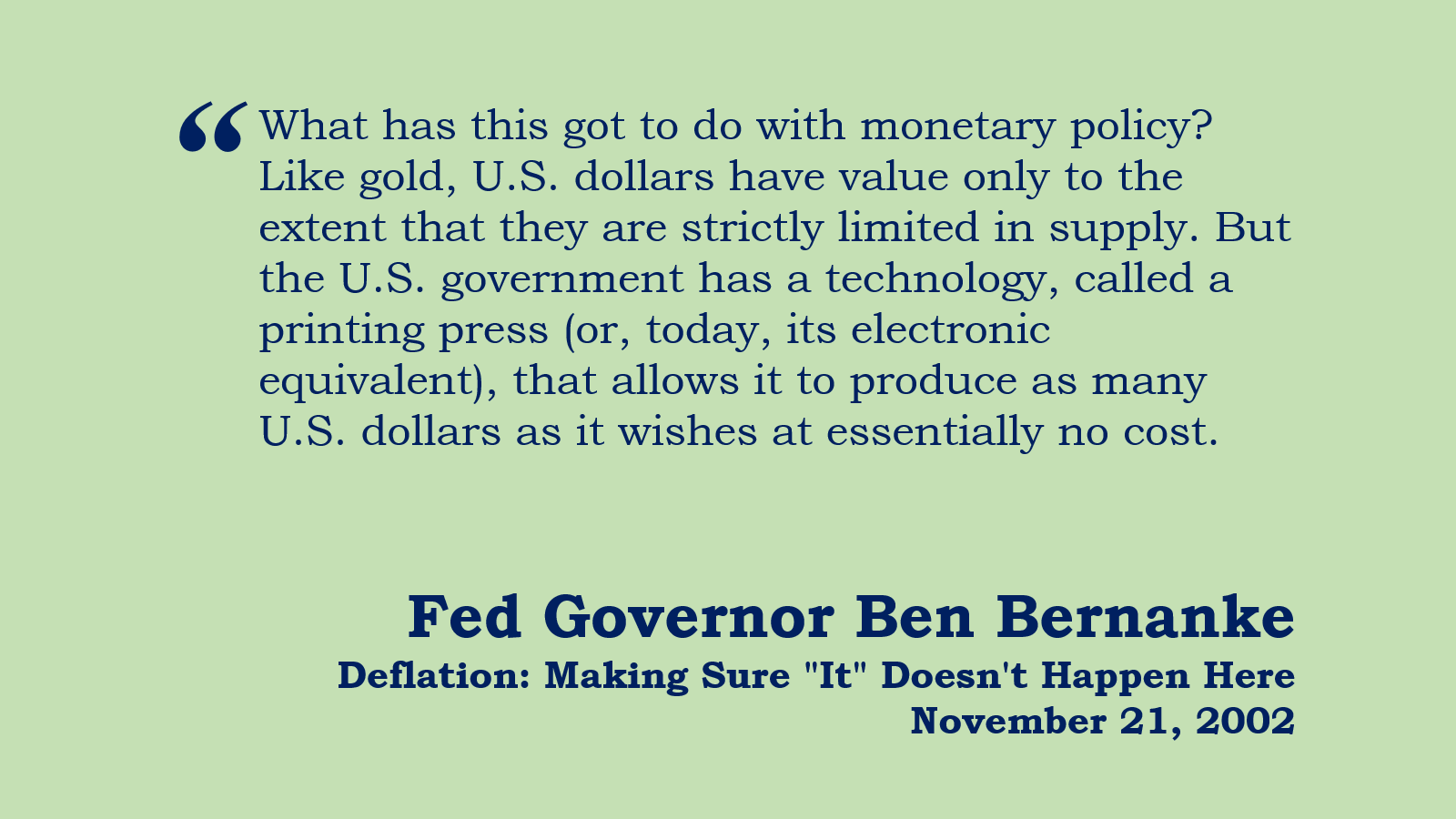

If, however, you believe the Fed has a printing press – as Ben Bernanke claimed for transparent purposes in November 2002, lying his ass off in the same way Jay Powell would in May 2020 – theoretically it makes interest rate policies seem more money-like therefore powerful if not plausible in order to achieve the true aims of all this theater. And that theater is, in the words of Mr. Bernanke circa 2004:

The ultimate objectives of monetary policy are expressed in terms of macroeconomic variables such as output, employment, and inflation. However, the influence of monetary policy instruments on these variables is at best indirect. The most direct and immediate effects of monetary policy actions, such as changes in the federal funds rate, are on the financial markets; by affecting asset prices and returns, policymakers try to modify economic behavior in ways that will help to achieve their ultimate objectives.

How does the Fed affect asset prices? The same way: Peter Pan. In the case of the stock market, old Peter has an easier time flying because people are already predisposed to trust in the fairy tale; they want to believe in it since it is psychologically easier to take financial risks (or sell them to other people) thinking an all-powerful money printer has the system’s best interests in mind when wielding that colossal tool.

What Bernanke said is correct: the Fed aims mainly to affect financial prices (they would like to influence bonds, too, as noted by the first paper above though the results in the bond market have been a series of “conundrums” instead). Those financial prices then create emotional elements hopefully causing positive trends leading to the desired (by officials) real economic outcomes.

This is very long way from the simple idea of lower rates = more borrowing everyone is led to imagine.

And this is why it rarely – if ever, as I constantly argue – works.

In another instance of you-don’t-have-to-take-my-word-for-it, Economists like policymakers have held internal discussions even debates after the poor, downright pitiful performance of interest rate (not monetary) policies during the 2010s. The public was only ever given glowing assessments especially about all the “money printing” in QE. Even the Fed in 2019 conducted a thorough review of its own execution and did not really like what it found (if you recall the whole thing about changing to a “symmetrical” inflation policy; again, beyond our scope here).

One of the Fed’s biggest critics from within mainstream Economics was and still is Larry Summers. When presenting his “secular stagnation” thesis way back in 2014 for the first time, Summers chastised the Fed for not doing enough therefore implicitly admitted the QEs weren’t all that effective. Maybe a few jobs saved (again, my interpretation of the evidence is far more damning) but definitely no recovery following 2008. And that was odd on its own terms because recessions require symmetry – in other words, if the contraction is sharp and deep, such as the 2008 panic-induced contraction, the recovery would therefore have to be equally sharp and robust.

SUMMERS DRAWS UPON THE DISCREDITED WORK OF ALVIN HANSEN TO PIECE TOGETHER AN EXPLANATION FOR WHY 'SECULAR STAGNATION' SEEMS TO HAVE SET UPON THE WORLD ECONOMY IN THE 2010s (and 2020s). HE SHOULD HAVE INSTEAD LOOKED TO...BEN BERNANKE. NOT THE FED OFFICIAL, THE FORMER SCHOLAR.

The fact it wasn’t is one the biggest story and blunder in all Economics this side of seventy-five years ago. Many inside the profession have sought to explain this, including many at the Fed, though never, ever in a way that might leak into the public. What Summers eventually wrote in 2020, following up on the matter because despite all the nonsense in 2018 about a labor shortage and full recovery, the evidence showed it never happened.

I am increasingly convinced that current macroeconomic theories, with their premise that monetary policy can determine the rate of inflation, may be unsuited to current economic reality and so provide misguided policy prescriptions. They failed to anticipate Japan’s deflationary slowdown that began in 1990, or the global financial crisis, slow recovery, and below-target inflation during a decade of recovery, or the sustainability of high levels of government debt with very low real interest rates.

Yep, basically everything everyone said about the 2010s (and well before) turned out to be wrong. From why there was a crisis in the first place (monetary panic not subprime mortgages) to QE-led recovery (which didn’t happen) even the repeated, constant drumbeat of “too many Treasuries”, all of them were completely wrong and every one of those for the same reason(s).

Then Summers fails to explain what that was (falling back on discredited Alvin Hansen’s 1930s theory; see: above).

Deflationary monetary conditions instead explain all the facts up to and including why the marketplace would continue to prefer US Treasuries even though the US government has gone completely mad and insane. Like the thirties under the New Deal, the financial marketplace could not care one bit about QE (the Fed bought loads of government bonds in the early years of the Great Depression, too) it only wants safety and liquidity which govt bonds provide.

Summers gets much of it right without realizing what he also gets wrong – starting with “monetary policy.” It isn’t. Attempting to manipulate one short run interest rate is as effective as screaming into a hurricane; the winds of deflation easily drown out even the most powerful voice.

And the Fed’s voice is hardly that.

By the way, Bernanke’s paper found that an “unanticipated” 25-bps rate cut should raise general stock prices by a little less than 1%. That’s even more underwhelming than it might already seem since this was written in 2004, meaning the data source for this claim is the Great Moderation of the 1980s and 1990s when stocks just went up the vast majority of the time. As usual, Bernanke was doing then what he always had while at the Fed, trying to turn correlation into anything which might legitimize a central bank in name only.