JUST CALL ME TROUBLE

EDU DDA Jan. 15, 2025

Summary: We have to question what the recession question even is before then asking the only question that gets to the root of the matter. First, the December CPI and an update from China with more money market turmoil. Afterward, getting to that potential unit question starting with Germany’s latest update then reviewing the history of “technical recession.” What we might call not-recovering is of secondary importance, at best, since what Germany shows is that whatever the labor it is indeed happening.

SO FAR, SCHOLZ IS RIGHT; NO RECESSION HAS BEEN DECLARED AND NO DECLARATION APPEARS FORTHCOMING. HE’S OUT OF A JOB ANYWAY BECAUSE THE RECESSION QUESTION MIGHT HAVE BEEN THE WRONG ONE.

Before we dive into Germany’s latest update and what that could mean for the rest of us, as you’ve probably heard today saw the release of the December US CPI report. The data themselves were not all that remarkable, at least from the perspective of anyone who’s been paying attention to what this disinflationary process really is and what form it has taken (lumpy). Yet, bonds rallied hard, even harder than they had in the wake of the June CPI from mid-July which was remarkable and had, in many ways, kicked off the trend what would eventually become the carry trade reverse and then the late summer rate panic.

For the rundown on the CPI and market reaction, I did a livestream on YouTube earlier today covering all that (replay available in the YT ad-free section of the DDA website). It was also in today’s Daily Briefing which you can access here.

China Update

There are a few updates from China worth mentioning, too. We left off yesterday with CNY maybe on the wrong side of the PBOC’s daily limit at the same time money market rates over there were becoming uncomfortably high (and the PBOC trying to be too clever in putting those two together in its favor).

Officials backed off somewhat if very slightly on the midpoint, lowering it by half a pip (0.0005) compared to yesterday’s. As it was, CNY rose a tiny amount anyway, which may have been more intervention through the broader encouragement to get financial firms to relend dollars (selling them). Whatever the reason or reasons, yuan’s unofficial onshore exchange ended up at 7.3310 and so just barely back on the good side of the lower bound.

For now.

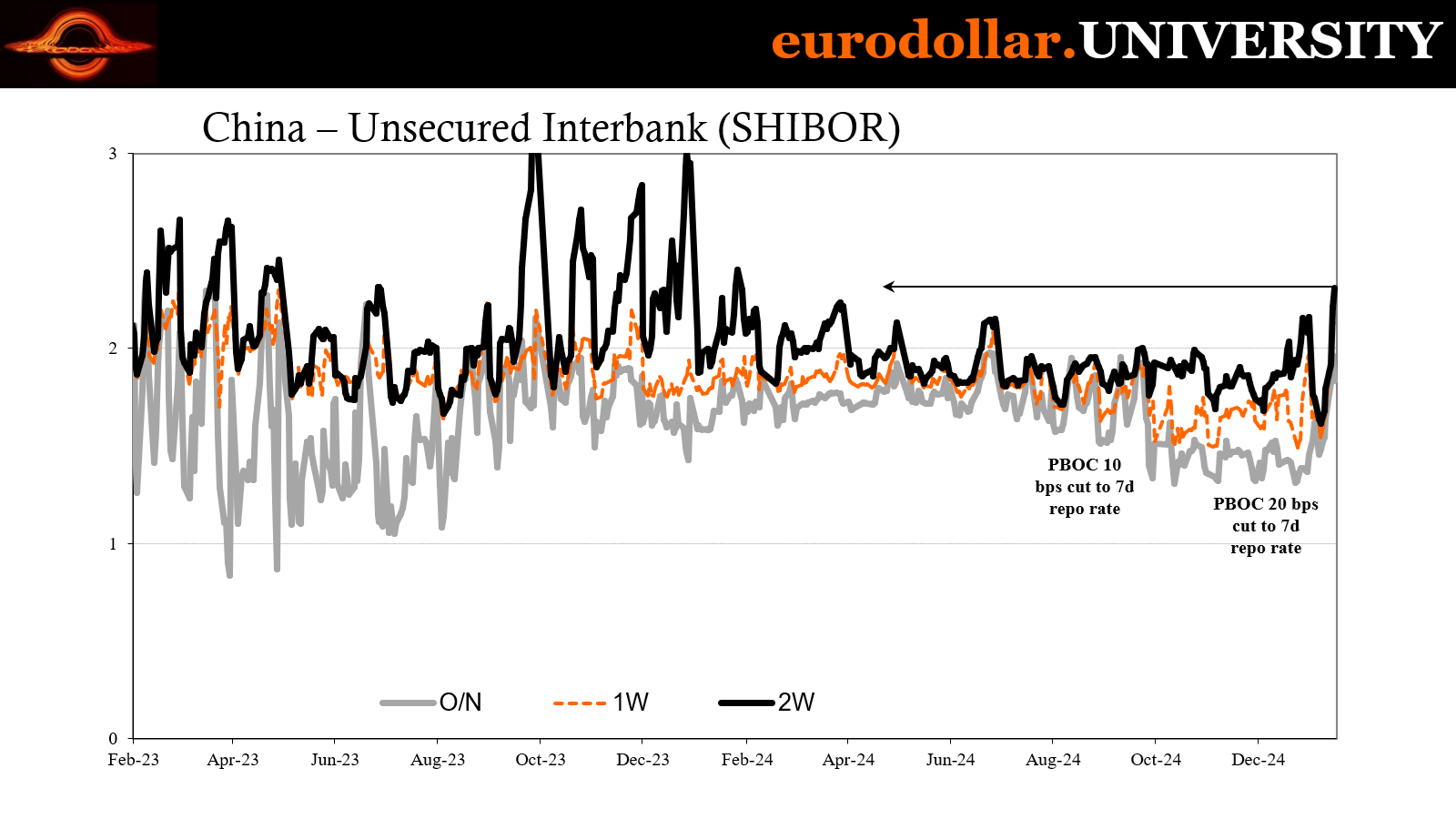

As far as the money market situation, illiquidity worsened seeing the 7-day repo rate rise further to 2.45% still two weeks out from the Lunar New Year Golden Week; the 14-day term repo rate climbed to 2.50%, a twenty-basis point increase. The overnight rate did slide back to 2.00% from 2.10%, indicating a reluctance to lend at even short-term beyond overnight.

Same in unsecured markets: O/N SHIBOR came back to 1.832% from its high of 1.965% yesterday, while the one-week rate was down 5 bps with both still elevated if moving in the right direction today. Meanwhile, two-week SHIBOR soared another ten basis points to a new recent high of 2.311%. More problems at term.

In response, after realizing yesterday’s press conference accomplished little or nothing to calm the situation, the PBOC today offered a massive seven-day reverse repo (lending cash to the market on collateral) totaling RMB 958.4 billion (net of one-year MLF maturities), the second highest net injection on record.

If that was the reason for the lower O/N rates yet did nothing for term, there might be something here.

And so much for saying their priority was CNY. Plus, the gigantic size of the operation further suggests yuan’s slightly higher value today was as artificial as it already appears. While the cash crunch is a combination of factors starting with the calendar, the overwhelming response by the central bank does point to growing anxiety there’s more to it than the expected tax payments and holiday hoarding starving the market.

The biggest risk – to China and the rest of the world – is the banking system’s credit crisis goes too far and triggers a real liquidity event. If the money market drama was happening at any other time apart from the leadup to the spring festival I’d be more concerned about that possibility. Still, bears watching closely and I’ll update the situation should anything else develop – including when the situation might calm down, as I do expect.

Germany more than Germany

The poster child for the supply shock’s aftermath. In many ways, like China, Germany took the wrong conclusion about it and ended up driving itself into the ditch, out the other side right into the trees and onto the edge of a major cliff.

The government saw immediately the promise of price illusion and took it for everlasting economic strength, choosing to use the possibility of that long-run potential to enact a slew of partisan priorities which we don’t need to get into here. Combine that voluntary (sort of) de-industrialization with the fact it was not, actually, a recovery, a reality that applies as much to the rest of the world and therefore the country’s biggest trade partners (like China who made the same exact mistake), Germany has been stuck in an odd situation.

I’ve repeatedly referred to their Industrial Production numbers as the saddest, most depressing macro series in the entire Western World.

And it is a disaster though it isn’t even classified as a recession. What the German government reported today was that GDP for all of 2024 ended up shrinking for the second year in a row, and at roughly the same small rate (-0.2% in ’24 following -0.3% in ’23). This leaves the economy in the odd predicament to where real GDP has contracted for two years in a row, yet in that entire time never for two straight quarters at any point.

There’s not even a “technical recession” despite how obvious something big and bad is going on.

Olaf Scholz had infamously declared near the start, in January 2023, there would be no recession in Germany. To this point, he’s correct; none has been declared. Yet, as Scholz’s government has already collapsed, how the economy might ultimately be classified seems entirely moot.

That raises a couple of more universal issues starting with simply defining recession to begin with, and what we might mean or what we’re really seeking to accomplish by doing so.

The very idea of a “technical recession” was first offered in the United States during the 1970s for just this situation. Coming off a recession at the start of the decade and then appearing to get hit with another one only a few years later, after the OPEC oil embargo in late ’73, the NBER was taking its time assessing the economic condition all throughout ’74.

For his part, President Richard Nixon emphatically stated in his State of the Union there wouldn’t be one in America during 1974 (Scholz was hardly the first). He got that one wrong, too, but how would anyone know without having to rely on a declaration from the famously sluggish NBER?

Richard Nixon really did not like even the idea of recession. In one sense, you can’t fault the guy since he was constantly blamed for them. This was a relatively new idea, too, that somehow Presidents are responsible for economic circumstances across the country. Earlier generations wouldn’t just have scoffed at the idea, they’d have known it was pitifully stupid.

What followed was indeed a recession, though one which was not immediately recognizable. For much of 1974, ambiguity was everywhere behind seemingly every indication. Labor data was mostly positive during the first several months of the year (in modern estimates, payrolls didn’t even put up a negative month until August ’74) and though GDP fell sharply in Q1 it rebounded in Q2 as nominal expansion clipped double digits.

The fourth quarter of ’73, the one with the embargo and skyrocketing fuel costs, GDP shot up by 12.4% (again, modern estimates) which was enough even with surging prices to produce better than 3% real growth. Against that backdrop, Nixon went before Congress in January for his State of the Union in which the President spent a lot time taking even more credit for the resilience of the economy.

Despite this record of achievement, as we turn to the year ahead we hear once again the familiar voice of the perennial prophets of gloom telling us now that because of the need to fight inflation, because of the energy shortage, America may be headed for a recession.

If it wasn’t for Watergate and his upcoming resignation, what Nixon said next might really have dogged him for the rest of this days, very much the same way “read my lips” clung to George H. W. Bush some years later. Speaking right to the American people, the President declared, “There will be no recession in the United States of America.”

Economist Julius Shiskin wrote for The New York Times in December ’74, “According to a recent Louis Harris poll, 65 per cent of the people in the United States think the country is now in a recession. Administration officials have acknowledged that we are in a recession, and most economists and newspaper correspondents now take it for granted.” Yet, Shiskin continued, no NBER determination was forthcoming (side note: when the NBER finally did date the contraction, they put the start in November 1973 meaning more than a full year had passed before the group did).

Instead, he quoted Geoffrey H. Moore, the NBER’s director of business cycle studies, who ploddingly confessed, “Until the contradictions in the data run their course, I don't think we're able to say we are in a recession.”

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

That’s the thing - one big thing, anyway – about recessions. The economic data is always ambiguous during them…until it isn’t. By the time the numbers are uniformly terrible it’s already too late and more likely than not the downturn is already almost over with.

Not satisfied with this state of Economics, in August 1974 Shiskin had previously taken to The New York Times having proposed a few simple guidelines. His reasoning was sound and even noble, wishing that politicians might not be rushed into making hasty, too-often harmful decisions having fooled themselves with their own optimistic biases – as Nixon would – in the absence of any useful standards and definitions.

At the time, Julius Shiskin had been a Commissioner at the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the agency which kept and keeps track of the Consumer Price Index along with the “official” government employment data. The outlines he proposed included just three parameters: 1. Duration: Exceeds nine months as measured by a decline in nonfarm payrolls; 2. Depth: At least a 1.5% drop in GNP which extends two quarters and also produces a rise in the unemployment rate above 6%; 3. Diffusion: Three-quarters of all industries must see rising joblessness also lasting six months or longer.

We all know the second one, or part of it, only too well today. This stripped-down “technical definition” of recession has been recited repeatedly ever since. Even Shiskin would tell you it isn’t so easy even if his main contribution was in an attempt to simplify judgement to the fullest extent possible.

A big part of the problem is that recessions don’t follow a template, no two are identical and they can take a number of different forms. The contraction in 1969-70 that hit Nixon shared few similarities with 1974 and 1975.

Then there is the more profound question of what a recession even means. Milton Friedman’s plucking model is maybe the best expression of what is thought to be its essential nature: a temporary deviation from the prior trend, therefore implicitly expecting afterward a full recovery takes place to quickly get the economy right back on that prior trend. There’s an element of symmetry implied in the model, for good reason.

Cycles had been nearly-enough symmetrical all throughout the postwar era, meaning the eurodollar’s world. From the Great Depression until 2007, that’s what recessions did and why Friedman came to be comfortable citing his “pluck.”

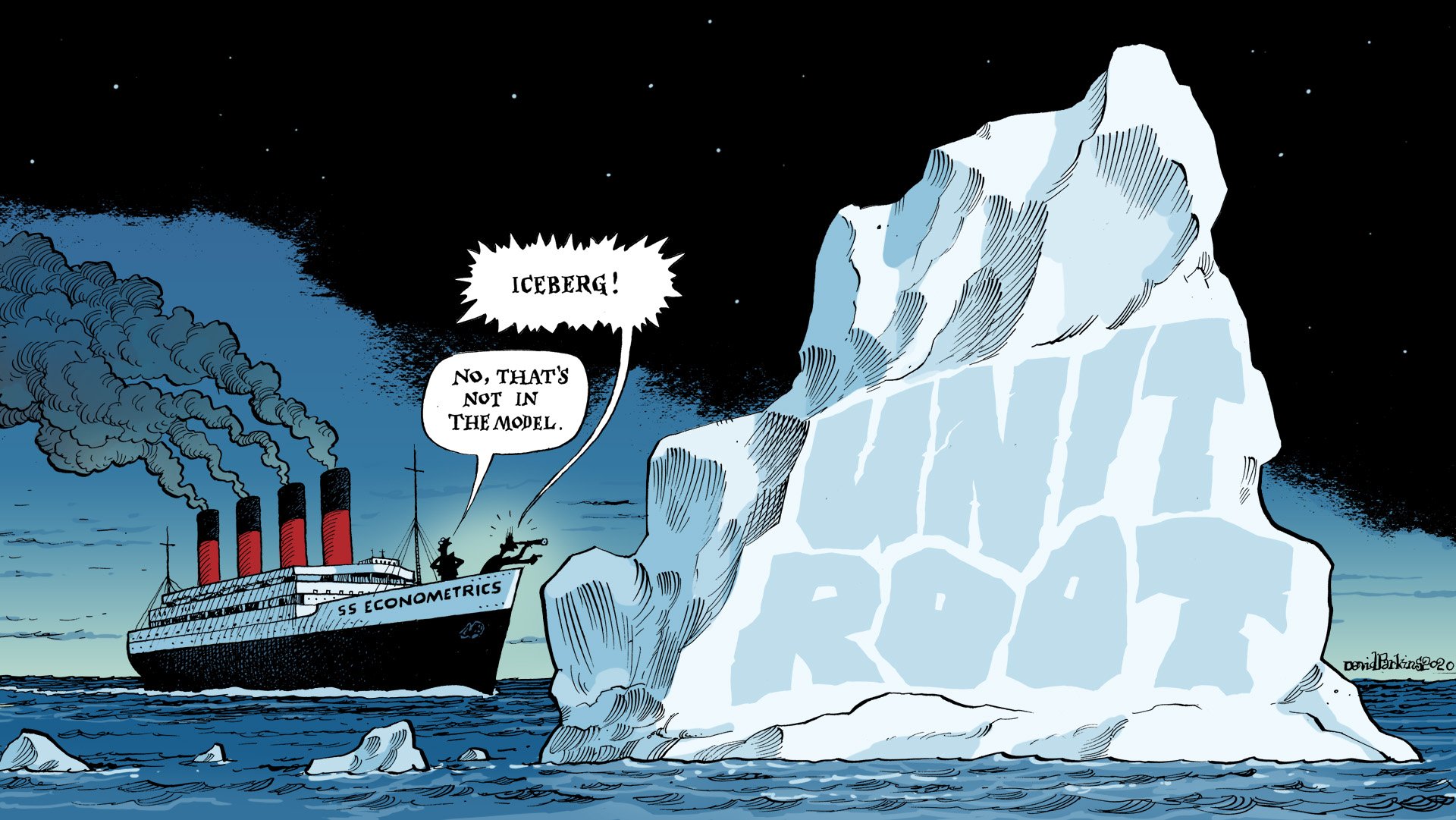

The Great not-Recession therefore opened the door to something other than recession (why I use “not” in the name, or scare quotes around “Recession” when not employing the “not”.) Economists call it a unit root (more on the concept behind “unit root” here) and then declare one impossible – despite all the evidence showing it absolutely has happened.

In other words, not only do we have enormous difficulty with recession, we have just as much and maybe more when it’s not recession.

Bringing this back to Germany, what if Germany’s odd cycle really isn’t one? What if Scholz is right about the recession question, but for the worst reason possible?

What I’m getting at is another unit root. The question of recession in 2024 and 2025 might be somewhat misplaced. I’ve said all along that what I expect is a transition from the artificial supply shock high of 2021, that price illusion of a recovery to something else with no recovery in between.

It’s certainly within the realm of what’s possible how a recognizable recession in the US or Germany ends up being part of that transition from price illusion to what comes after it. We have the labor market difficulties in both places, more unemployment in the latter than the former yet visible distress in each nonetheless.

As difficult as it is to identify a recession, even as developed as the downturn had been in 1974, how much more difficult might it be to get a sense of the possibility for another unit root?

I actually examined the prospects for something like that when comparing the slowdown/downturn to the early 21st century dot-com bust. Unlike stock crashes, the stock bust and indeed the recession following from it hardly looked like the sharp, clean drop everyone imagines. On the contrary, both were slow and prolonged, shallow yet unrelenting.

Starting to really sound familiar.

That’s just what we’re seeing in Germany and especially German GDP. And what that shows is this transition really does appear to be happening and in a big enough way to register in GDP even if it really might not fit neatly into any box. What if an economy just stops growing? That is the implication staring right back at us from the data.

It’s the same thing we see in the US labor data if not (yet) in its GDP. I am absolutely including the Establishment Survey in this category, too. Every one of those series, from payrolls to hours, HH Survey employment and beyond, that’s just what they show: the labor market abruptly stopped recovering same as German GDP. It took a little while longer to register, roughly another year further into the downside, but ending up with the same general pattern and idea nonetheless.

Germany does have its own issues, as stated above. Those very well could explain why it has gotten to be as bad as it has, this protracted non-recession. Keeping those idiosyncrasies in mind, I still believe that only accounts for maybe timing along with intensity, not the pattern itself.

Whether that pattern is a recession might be entirely beside the point. Look at copper-to-gold or swap spreads down at 2020 or 2009 levels. Fitting the current transition phase into some pre-conceived definition isn’t necessarily helpful, potentially a distraction. And it was enough of one to keep people like Scholz in office far longer than they should have been.

Germany shows the possibility is right there, the best example from the rest of the world for whatever we call it. Whatever its label, it sure as hell looks like another phase shift. The fact it aligns with all of the US labor market is all the more remarkable and profound.

What do we call a recovery that just stops recovering? The world of Economists may not call it a recession, yet politicians are finding out the hard way they really should’ve been calling it trouble.