A CAYMAN JAPAN CONNECTION MADE IN EUROPEANS’ US BRANCHES

EDU DDA Nov. 21, 2024

Summary: Repo fails were lower for the second straight week. That means we can check the correlations with other indications like bills, Treasury and Japanese, going in the other direction. Maybe more importantly, TIC figures show a massive deposit of USTs in the Cayman Islands. When? July, August, and September, the very period in question. The question for today’s DDA is how to connect all these pieces. We do just that with a big assist from…the ECB.

Repo fails dipped again in the latest weekly data, the second month in a row at a reduced pace from the big surge to end October. While lower, the rising trend for now seems to be still intact. This relaxation does give us a chance to calibrate fails with other collateral indications, including J-bills and T-bills. If fails are lower, did those back off, too?

Spoiler: yes.

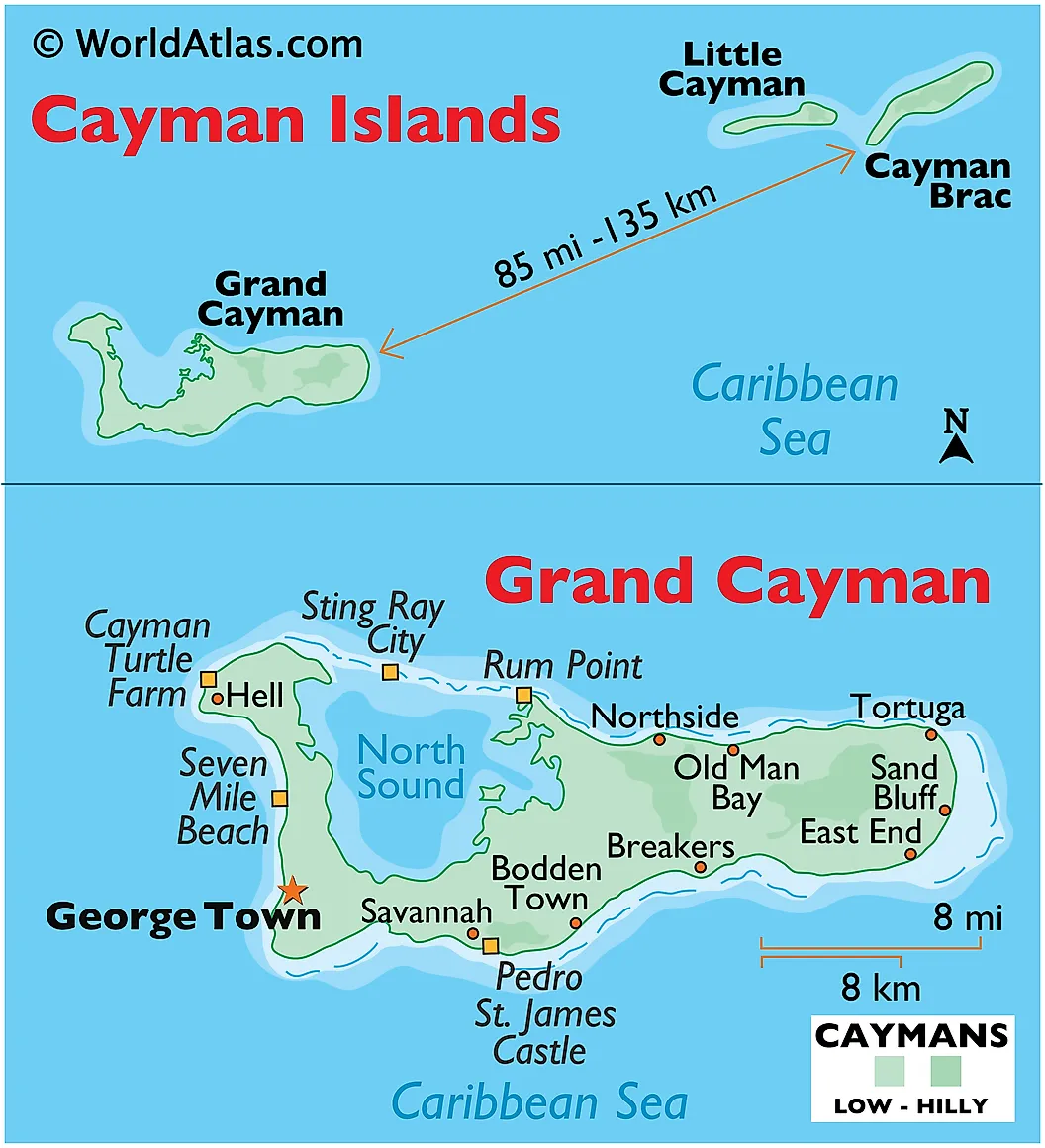

There is another one, a big one as it turned out (and one I am ashamed I had missed when it was originally reported last month). An absolute deluge of UST securities hit the Cayman Islands’ stable of virtual banks. An astounding $100 billion combined poured onto Grand Cayman in July and August, the carry trade buildup. They remained there in September, too, with a few extra billion piled on.

That comes from the TIC estimates through September 2024 which also featured more large selling from Japan and China (the subject of the YT livestream I did earlier this evening; if you haven’t seen it, the replay is available in the YT ad-free part of the DDA site). “Selling Treasuries” has little to do with Treasuries and everything to do with what we’re focusing on here.

And what we’re getting to starts with a detour into Europe, of all places. The eurodollar has been making a comeback there, where I mean specifically the European part of it. It started out way back in ancient history centered on London, particularly, with substantial nodes of this “Continental dollar”, as it was also known, in France, Switzerland, and Germany.

The European center was the entire reason why the convention of calling anything offshore “euro” caught on.

The Cayman Islands came in relatively late, while eurodollar capacities had more quickly spread to Japan and Canada. It was the 2008 crisis which shuffled everything to the point the eurodollar was really becoming more of an Asian dollar (or Asia-centered eurodollar). The balance of economic therefore monetary gravity had shifted East in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis.

Western countries were a total mess struggling to recover and their banks, those which had been the backbone of the system before then, dramatically impaired. The Japanese took the lead in 2009 jumping in to the eurodollar redistribution business where European banks had once dominated. The former’s closer ties to China made them the obvious choice.

So long as China lived up to these initial post-crisis expectations it would have worked really well. Those expectations had started with the idea the Chinese would continue to grow relentlessly regardless of the rest of the world – a Grand Decoupling, if you will. It should have been seen as a longshot from the beginning. Though, in truth, no one should have bought into it.

Instead, it took a few years before China would finally show signs of joining the worldwide Silent Depression. And a few more beyond those to display helplessness in Beijing to do anything about the reversal. A key moment in this realization process came in late 2013 when rumors began to swirl around Shanghai Chaori Solar Energy Science & Technology. Its eventual default early in 2014 was pivotal in ushering the late 2010s retreat of the Asian dollar not to mention China’s overall.

Shanghai Chaori was a big reason why, for example, CNY went from invulnerably strong before 2014 to reversing and never being able to recover to this very day. Its default showed that risks were indeed real and substantial for a Chinese economy that really was getting pulled into the Silent Depression. It was a true watershed (below from March 2014):

Up until now, the Chinese government and state-owned banks have helped bail out or provide last-minute loans to Chinese firms in trouble.

That has led many investors to park their funds in the corporate bonds of many Chinese firms, on the belief that the government would help ensure that these firms could continue to repay their debts.

However, a significant portion of this debt is set to mature in 2014 - with more than $1.5 trillion of corporate bonds outstanding at the end of January.

"There's not enough money in the world to bail everything out," said Mr. Miller.

Truer words than Mr. Miller’s have rarely been spoken. In this case, it wasn’t just the government money for bailing out every last zombie and waste-filled domestic corporate. More and more, not enough “eurodollars” for China or anywhere else, either, the dramatic, devastating shift we call Euro$ #3 which was led by the Japanese.

Having moved the eurodollar center East, the Japanese began to realize the error around the time Shanghai Chaori was getting be all over the world financial press. This was a big reason why 2015 and especially 2016 had been such a huge problem also for Japan’s eurodollar banks – the genesis of the collateral problems I discussed here covering the 3-month J-bill’s connection to repo fails and US$ collateral in general.

In short, risk aversion all the way around. Who had what exposure to which part of the Chinese colossus as it was completely reversing course?

Without the Japanese, the entire eurodollar world remained in limbo into the 2010s, without the same Asian dollar resources or the Chinese economy’s longed-for growth status. Over the past few years, however, European banks have come back into that role. Even more curious, they’ve been doing it via their US-based subsidiaries and branches.

Those subs and branches have been borrowing heavily in repos and even unsecured (commercial paper) to the point that, according to the most recent ECB report on the matter, nearly a quarter of European bank activities are now being funded in foreign currencies, with 17% in US$ denomination alone.

Why?

Not to redistribute to China, rather to non-banks around the Western world. Investment funds are the new hot thing (even though they’re obviously old), the “cleanest” balance sheets around and the only ones with space to do much of anything. Unlike banks of the eurodollar’s peak era, they can’t create money therefore have to depend on wholesale markets for everything, max leverage. Those markets rely on dealers first and foremost to keep the money and collateral flowing (why we focus on swap spreads since they are one gauge of dealer balance sheet capacities).

From the ECB:

After a decade in which their presence in the United States declined, euro area banks have recently expanded the balance sheets of their branches and broker-dealer subsidiaries (Chart A, panel b, left graph). The business models of the US affiliates differ markedly: while bank subsidiaries engage in traditional deposit-taking and lending operations, broker-dealer subsidiaries focus more on capital market activities and are heavily involved in repo markets as intermediators. Bank branches appear to follow a hybrid business model of capital market activities alongside lending to larger clients on aggregate (Chart A, panel b, right graph). There are notable differences across jurisdictions however, with branches of French banks the most active in repo markets. By contrast, branches of German banks focus more on lending and rely to a larger extent on headquarter funding.

One reason to keep a closer eye on the French (and French bond spreads?)

This also gives us a strong sense of where the cash is coming from that Japanese carry traders, for example, have been forced to borrow in lieu of US$ repo (collateral scarcity)? The key connection between J-bills and US$ collateral/funding is FX markets; Japanese borrowers are able to swap yen for scarce US$ collateral using FX rather than repo.

And that cash in FX comes from:

US dollar repos are largely (70%) collateralised by government bonds (of which 95% are Treasuries). The bulk of this is not centrally cleared (87%), implying a higher counterparty risk than is the case for centrally cleared transactions. The vast majority of repos are short-term, with 85% having a maturity of one week or less (Chart B, panel b). Euro area banks play a key role in intermediating US dollar liquidity. They do so by receiving cash largely from their US-affiliated security broker-dealers and lending the dollars to non-banks, the majority of which are offshore investment funds (Chart B, panel c). As cash borrowing exceeds cash lending, euro area banks have excess US dollars at their disposal, which they can sell in the FX swap market. [emphasis added]

Traditionally, European banks have preferred their offshore business in…the Cayman Islands. This is the main reason why the eurodollar footprint there shrunk so much after 2011 as the system headed toward Japan (for a few years).

With all that in mind, Japanese carry traders were confronted by the consequences of unwinding carry trades more heavily starting in July then August. They were forced to work around repo funding into FX, substituting yen for USTs. The dollars the Japanese got in FX almost certainty came from the European banks the ECB is highlighting above.

But then who was depositing those tens of billions in UST collateral in the Cayman Islands? That is the question. It wasn’t Japan; the Japanese had yen as substitute collateral so didn’t need to post USTs to borrow FX from the Europeans. It seems instead whomever it was got caught up in the market’s illiquidity and those someones were forced like the Japanese to borrow in FX though they had to scramble for collateral to do so.

Which non-banks and where? The answer to that one will have to remain hidden for now.

And that scramble is almost certainly what we see in the repo fails trend, maybe T-bills, too, and why those have corresponded with the J-bill if for indirectly related reasons. The fact that the collateral posting to Grand Cayman began in July before the inflection in repo fails indicates the pressure was indeed building (seen in swaps) before early August; the US jobs data was just one negative too many for system already under strain, finally triggering the initially disorderly unwinding and collateral (pun intended) consequences clearly felt all around the world.

More recent evidence suggests that pressure has lessened here in November. As I started out at the beginning, repo fails for the two weeks this month are back under $200 billion again, a significant improvement from the $300 billion to close out October. That’s still elevated compared to the period before August, though.

This drawdown in fails and by proxy collateral scarcity gives us a chance to measure the correlation with those other indications only now going in the other direction. In other words, if rising scarcity forces the carry traders to substitute yen for UST collateral, FX instead of repo, then less scarcity as seen in lower repo fails should lead to higher relative J-bill yields.

Sure enough:

The same goes for T-bills, too. In that corner, we’ve seen substantially less intense buying interest including at today’s 4- and 8-week auctions (both saw rising clearing yields compared to last week). Not only that, the spread between the 4-week and 8-week bill, or 4-week bill and term-SOFR, have increased during November, too. The 4w had, during late October, compressed to the 8w and term-SOFR, even overtaking the 8w on a couple occasions.

While there are, as always, significant gaps in our narrative’s coverage and, as always, a lot of unknown information as the reason why, what we do have is becoming a complete enough picture as to raise our confidence in that description.

And that is the money and financial world is (was?) not so sanguine about the global economy’s prospects since this summer; which also fits what the macro data is increasingly showing especially in the US (now better revealed by the QCEW update I covered in yesterday’s DDA).

Did all that change in November? Was it because of Trump?

Those are the questions we’re facing right now. I don’t see anything that suggests a categorical change in conditions. Even lower repo fails aren’t unusual, or the better flow around the rest of the system which might result for slightly less dealer pressures. Filling in some gaps and confirming a lot of the story does greatly help with being able to analyze these signals as we roll forward from here.